More about The Rhinoceros

Sr. Editor

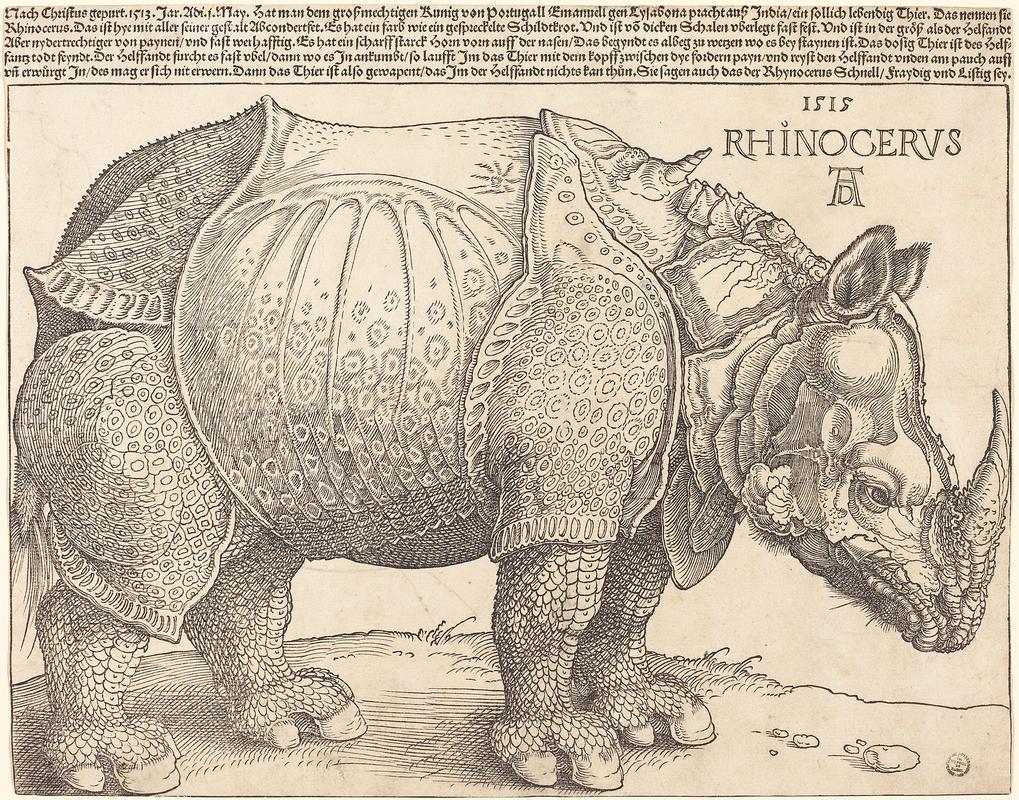

Albrect Dürer’s The Rhinoceros isn’t exactly zoologically accurate.

Albrect Dürer lived in the 15th and 16th centuries, so it's not like he could just Google what a rhinoceros looked like. The drawing was created during the German Renaissance, however, when there was a growing thirst for scientific knowledge and interest in other cultures due to growing international trade.

The subject of this drawing was the first rhinoceros to land in Europe in over 1000 years, since the 3rd century AD in Roman times, so folks were understandably fascinated by the exotic beast. With the advent of the printing press around this time, which allowed the mass reproduction of images, it's also not surprising that Durer's rendition of the rhino became one of the most popular and widespread artworks of the era. The British Museum even goes so far as to call it "one of the most influential images in the history of western art." So, how did it come to be?

The rhino in question was a diplomatic gift to the governor of Portuguese India from the Sultan of Cambay (modern day Gujarat). The governor, realizing the impracticality of keeping a rhinoceros for a pet (and perhaps wanting to kiss a little royal butt), decided to ship the animal and its handler to King Manuel I in Lisbon. It was not unusual for foreign rulers to exchange exotic animals as gestures of good will, and King Manuel was thrilled to add another member to his menagerie at Ribeira Palace. He even paraded the rhinoceros around the city, along with an entourage of five elephants and many dudes on horses.

All of this, as you might imagine, caused quite a stir. As aforementioned, a rhinoceros had not been seen in Europe in centuries, and as such had become a somewhat mythical beast in the cultural imagination, often being conflated with the unicorn. The Renaissance fascination with antiquity stirred a special interest in the animal that was last written about in Roman times - the rhino was rediscovered, so to speak, and ready to be studied.

Famed Roman scholar Pliny the Younger (nephew of the Elder) had recorded that the elephant and rhinoceros were bitter enemies, and would fight to the death if given the opportunity. In an decidedly unscientific "experiment," and as an effort to cheer up Queen Maria who had recently lost a child in infancy, King Manuel put this theory to the test, pitting the two animals against each other in a public fight, gladiator style. This was obviously cruel, especially to the poor elephant, who got so spooked by the noise of the crowd of spectators that it broke through the barriers of the arena, escaping to the streets of Lisbon where shocked citizens were forced to leap out of its stampeding path. This exciting incident caused the news of the rhinoceros to spread even faster and farther throughout Europe, which is how Durer got wind of it in Nuremberg, after a letter including a sketch of the animal was passed on to him by an unknown acquaintance.

There is some debate about the reason for the anatomical inaccuracy of Durer's drawing, but the most commonly held explanation is simply artistic license. One author suggests that the riveted plates of armor were actually present - outfitted on top of the rhinoceros in preparation for his duel with the elephant, but it's an unproven theory (and doesn't make a whole lot of sense, as elephants don't have horns). Others think Durer was creatively trying to express the thick folds of the rhino's hide, or that the circular pattern is his representation of a skin condition that may have developed on the arduous boat ride over from India. Again, we just can't be sure.

In any case, due to its popularity, this is the picture that popped into the heads of Europeans at the mention of the animal until the late 1700s, when more rhinos were shipped over. The image remained in German textbooks until the 1930s, and was also an inspiration to Salvador Dali, who had a copy of the print in his house growing up and recreated Durer's rendition in some of his works. Dali was somewhat obsessed by the print, writing: “The rhinoceros is the only animal that carries an incredible amount of cosmic knowledge within its armor," and was similarly fascinated by its horn, which he described as "“the essential basis of every chaste and violent aesthetic.”

Sources

- Bedini, Silvano A. (1997). The Pope's Elephant. Manchester: Carcanet Press.

- “Dalí's Fascination with the Rhinoceros.” The Dalí Universe, September 29, 1970. https://www.thedaliuniverse.com/en/news-dalis-fascination-the-rhinoceros.

- Sherwin, Skye. “Albrecht Dürer’s The Rhinoceros: the most influential animal picture ever?” The Guardian. November 11, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/nov/11/albrecht-durer-the…

- The Art Story. “Albrecht Dürer Artworks”. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/durer-albrecht/artworks/#nav

- Willis, Matthew. “Dürer’s Rhinoceros and the Birth of Print Media” JSTOR Daily. June 28, 2016. https://daily.jstor.org/durers-rhinoceros-and-the-birth-of-print-media/

Featured Books & Academic Sources

This is a 1991 poem written by Lars Gustafsson and translated by Yvonne L. Sandstroem, published in the Southwest Review:

Dürer's rhinoceros, singular animal so solemnly

filling the picture space with your grave body,

you hide in plates of heavy armor like those of some knight,

some man of gravity soldiering forth. What maiden

will you find, you, the only real unicorn?

It's plain you've come from far away

and don't belong in these dark Frankish valleys.

What would it take to penetrate

that body, to reach your heart?

A silver bullet? Snaring you in some

patiently woven net cannot have been easy,

still keeping you alive all the way here.

And all this just to snare you again

in the picture's terrible net,

and this time forever.

What did you think? How still did you stand? What fear

must you have felt in your too well-armored heart?

The Master made you a knight,

larger, more melancholy, more armored

than any others in his pictures.

Perhaps more innocent as well.

You are The Animal That's Standing Still

amid the cold stream, trapping

in very small but faithful, watchful eyes

each picture the light reflects into the water.

Your own knight. Your own dragon.

Ready for anything.

Sources

- GUSTAFSSON, LARS, and Yvonne L. Sandstroem. “Albrecht Dürer’s Rhinoceros, 1515.” Southwest Review 76, no. 1 (1991): 139–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43471432.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Dürer's Rhinoceros

Dürer's Rhinoceros is the name commonly given to a woodcut executed by German artist Albrecht Dürer in 1515. Dürer never saw the actual rhinoceros, which was the first living example seen in Europe since Roman times. Instead the image is based on an anonymous written description and brief sketch of an Indian rhinoceros brought to Lisbon in 1515. Later that year, the King of Portugal, Manuel I, sent the animal as a gift for Pope Leo X, but it died in a shipwreck off the coast of Italy. Another live rhinoceros was not seen again until Abada arrived from India to the court of Sebastian of Portugal in 1577.

Dürer's woodcut is not an accurate representation. He depicts an animal with hard plates that cover its body like sheets of armor, with a gorget at the throat, a solid-looking breastplate, and what appear to be rivets along the seams. He places a small twisted horn on its back and gives it scaly legs and saw-like rear quarters. None of these features are present in a real rhinoceros, although the Indian rhinoceros does have deep folds in its skin that can look like armor from a distance.

Dürer's woodcut became very popular in Europe and was copied many times in the following three centuries. It was regarded as a true representation of a rhinoceros into the late 18th century, and it has been said of Dürer's woodcut that "probably no animal picture has exerted such a profound influence on the arts". Eventually, it was supplanted by more realistic drawings and paintings, particularly those of Clara the rhinoceros, who toured Europe in the 1740s and 1750s.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Dürer's Rhinoceros