Feminist art theory emerged in the 60s in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War. During this period of protest, Linda Nochlin published the seminal article “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” exploring the institutional biases that prevented women from achieving the success of their male counterparts. Nochlin questioned these institutions through the inherent male gaze of art history, which viewed the world through the lens of the white western heterosexual male. The male gaze prefers mediums like painting and sculpture, which were predominately male due to the historical exclusion of women from life-drawing and therefore the necessary study of anatomy. The subjects women were able to paint, like domestic scenes drawn from their daily lives, were deemed as “feminine” and inferior. The male gaze in art positions the artist and viewer as male and women as muses and objects of desire, exemplified by the prevalence of the female nude. The legacies of women artists are also often undercut by the narrative of their entanglement with male artists.

Feminist art theory emerged in the 60s in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War. During this period of protest, Linda Nochlin published the seminal article “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” exploring the institutional biases that prevented women from achieving the success of their male counterparts. Nochlin questioned these institutions through the inherent male gaze of art history, which viewed the world through the lens of the white western heterosexual male. The male gaze prefers mediums like painting and sculpture, which were predominately male due to the historical exclusion of women from life-drawing and therefore the necessary study of anatomy. The subjects women were able to paint, like domestic scenes drawn from their daily lives, were deemed as “feminine” and inferior. The male gaze in art positions the artist and viewer as male and women as muses and objects of desire, exemplified by the prevalence of the female nude. The legacies of women artists are also often undercut by the narrative of their entanglement with male artists.

Dior’s first female creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri references Nochlin in the Spring/Summer 2018 collection

Feminist artists subverted the male gaze through their art, seeking to rewrite male-dominated art history. Women created alternative venues to show their work as well as worked to change existing institutions to promote the visibility of female artists in the market and embraced alternative materials that were seen as feminine including textiles, performance, and video, which did not have the same male precedents that painting and sculpture had.

Judy Chicago, Shelia Levrant de Bretteville, and Arlene Raven did this by creating art from a female perspective in their 1977 exhibit “What is Feminist Art?” at the Los Angeles Women’s Building. The exhibit began as a project by activists Ruth Iskin, Lucy Lippard, and Arlene Raven in which they sent pink postcards with the prompt: “If you consider yourself a feminist, would you respond by using one 8 1/2” x 11” page to share your ideas on what feminist art is or could be.” The Los Angeles Women’s Building became a mecca of feminist art, offering art courses and a studio for women.

Since the experiences of women are not the same, feminist art took on many mediums and approaches. One of the most famous pieces of installation art, The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago featured thirty-nine place settings of women in history at a triangular table. The table was divided into three sections of history–prehistory to Classical Rome, beginning of Christianity to Reformation, and American Revolution to Women’s Revolution. Below the table, the Heritage Floor was inscribed with the names of 998 women and one man. By placing female historical figures at the table, Chicago questions the male-focused narrative of history.

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974-79.

Another approach was to subvert the patriarchal tropes by satirizing the myth of the male artistic genius. In the boys’ club of Abstract Expressionism led by figures like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, women artists like Pollock’s own wife Lee Krasner and de Kooning’s wife Elaine de Kooning were marginalized within the artistic community, were overshadowed and their identity as artists seen as attached to their husbands rather than as real independent artists. Elaine de Kooning resisted this narrative, painting her male subjects through the same voyeuristic lens, remarking in 1987, “women painted women: Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Mary Cassatt, and so forth. And I thought, men always painted the opposite sex, and I wanted to paint men as sex objects.” In Mary Beth Edelson’s Some Living American Women Artists, subversion takes form in a parody of da Vinci’s canonical painting The Last Supper. Edelson collages the faces of her friends and colleges over the faces of Jesus and his disciples. Georgia O’Keeffe is Jesus, and other artists, including Alma Thomas, Yoko Ono, Faith Ringgold, Agnes Martin, and Alice Neel, are randomly placed. There is also no one in the role of the traitor, Judas. In her self-described “spoof of the male exclusivity of the patriarchy”, she addresses the role of religion as a cultural force in the subordination of women.

Mary Beth Edelson, Some Living American Women Artists, 1972.

Feminist art can also be activist art when it seeks to incite change. During this period, much of the activist art was intersectional, and many of the artists and techniques between each of these movements were intertwined, often addressing multiple issues as artists often identified with the experiences of other groups.

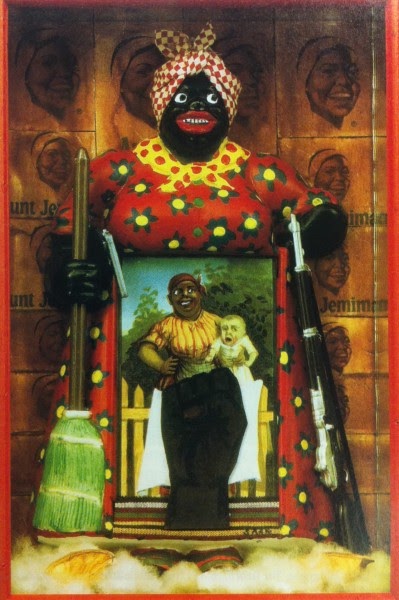

Betye Saar, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972.

Betye Saar’s The Liberation of Aunt Jemima is an iconic piece of feminist and art and a symbol of Black liberation. It is an assemblage that positions the “Aunt Jemima” mammy figure as a derogatory figurine of an armed warrior. The mammy caricature was a commercialized image of a Black woman used to sell objects, like the broom that she holds and the pancake mix that makes up the background, that serves their owners. The mammy was used to enforce oppressive stereotypes of Black women as obedient and submissive servants whose only purpose was to care for their owner/employer. Saar’s Aunt Jemima is a rejection of this trope, wielding a gun to symbolize power and a mixed-race child to represent the sexual assault and subjugation of Black female slaves by white men. In her reconstruction of a self-liberating Aunt Jemima, Saar rejects demeaning stereotypes and systematic oppression.

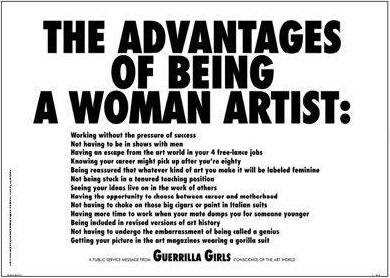

Guerilla Girls, the Advantages of Being A Woman Artist, 1988.

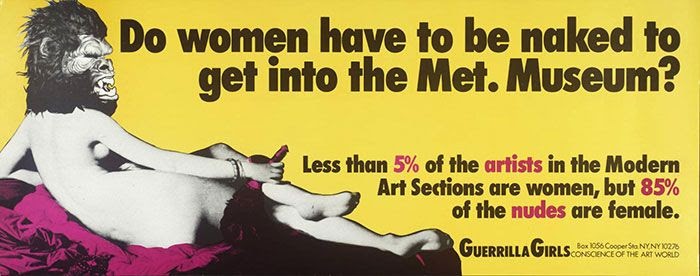

Artists employed the techniques of Pop Art, using popular culture to spread their message. The Guerrilla Girls were a group of anonymous female artists focused on sexism and racism in the art world. They used humor and wit in their work and wore gorilla masks in public, taking the aliases of famous female figures to keep the focus on issues rather than their personalities. The Guerilla Girls publicized the inequities of the art world through posters in NYC. In The Whitney Museum Gets a New Name, the demographics of the artists are displayed, exposing the return to the dominance of male artists at the Whitney Biennial in 1995 after the 1993 exhibit, which had an unusually high number of female artists and was denounced by art critics. The 1989 poster Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum? is a response to the popularity of female nudes by presenting an image of the Grande Odalisque by Ingres, one of the most famous nudes in history, with a gorilla mask placed over the head. It was originally commissioned by the New York Public Art Fund but was rejected for not being clear enough, to which they responded by renting out advertising space on New York buses themselves until the bus company canceled their lease because the image was seen as too suggestive (partially because of the “fan” in her hand).

Guerilla Girls, Do women have to be naked to get Into the Met.Museum?, 1989.

Contemporary artists still create art about gender. The Guerilla Girls have continued to create art which protests the practices of institutions that exclude female artists and present women as voyeuristic objects. Female artists are still creating art as a form of resistance against the inequalities of the art world and the world at large. Feminist art is not an art movement with a distinctive style, rather it is art that is created through the lens of feminist art theory. Artists have utilized art as a form of institutional critique against exclusionary practices that have prevented women from achieving the same success in art. Feminist art began in the 60s during a time when activism and art were intertwined but has continued into the present as female artists continue to fight against institutional barriers.

Sources

- Brand, Peg. "Feminist Art Epistemologies: Understanding Feminist Art." Hypatia 21, no. 3 (2006): 166-89. www.jstor.org/stable/3810957.

- “Feminist Art.” The Art Story. https://www.theartstory.org/movement/feminist-art/.

- “Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum?” Tate. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/guerrilla-girls-do-women-have-to-b….

- Gibson, Ann Eden. Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997.

- Gotthardt, Alexxa. “How Betye Saar Transformed Aunt Jemima Into a Symbol of Black Power.” Artsy. Oct 26, 2017. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-betye-saar-transformed-au…

- Greifen, Kat. “Considering Mary Beth Edelson’s Some Living American Artists.” The Brooklyn Rail (March 2019). https://brooklynrail.org/2019/03/criticspage/Considering-Mary-Beth-Edel….

- “Mary Beth Edelson.” Clara: Database of Women Artists, National Museum of Women in the Arts.

- Nochlin, Linda. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” ARTnews (January 1971): 22. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/retrospective/why-have-there-been-no-g….

- “The Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution Presents What is Feminist Art?” Smithsonian Archives of American Art. Oct 14, 2019.

Comments (4)

Impressive work!

Love seeing the feminist twist on things.

Do you also think this is a feminist work https://www.sartle.com/artwork/great-american-nude-75-tom-wesselmann?

I am, of course, ready to accept this part of feminine art, but to remake a Da Vinci painting is too much for me.