Cubism was one of the first -isms to hit our collective senses in the twentieth-century art world. It all began when our playboy Pablo Picasso and dear Georges Braque began using cubes and simplistic forms in their paintings. Revolutionary! These brothers-in-crime believed that by breaking down objects into distinct planes they could demonstrate to the viewer that different viewpoints could be seen at the same time. In less art history speak: geometric shapes rule, man.

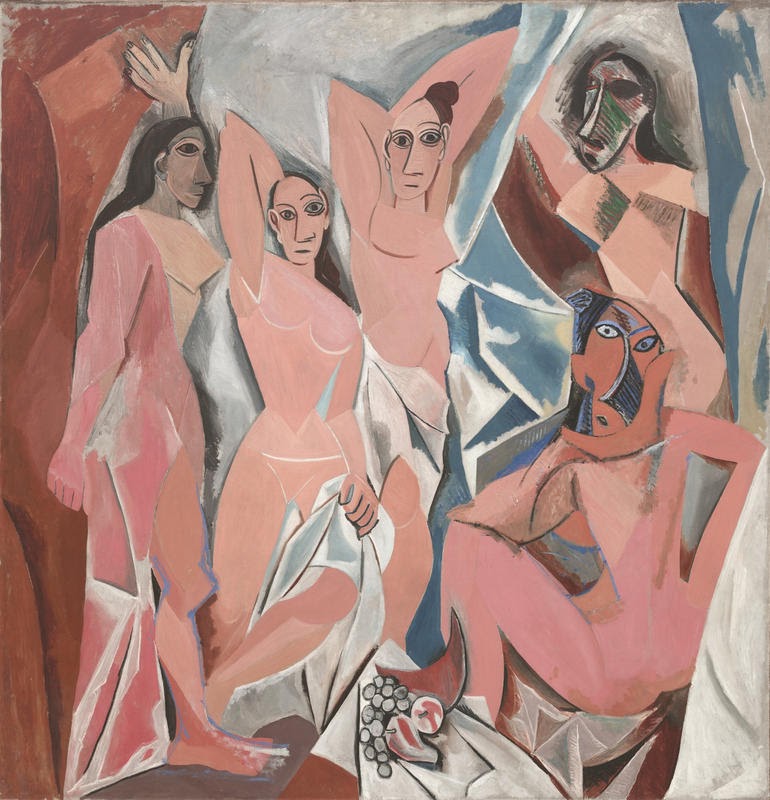

Picasso and Braque’s friendship was intense, and yet ultimately short-lived. Like any passionate relationship, there were great highs and the lowest of lows. Although their bond was reportedly close, they weren’t above hurling snide remarks each others’ way. Their relationship ended abruptly with the outbreak of World War I, and Braque is quoted to say, “Picasso and I said things to one another that will never be said again . . . that no one will be able to understand.”  Braque was the only artist throughout Picasso’s lifetime with whom he shared a deep, intimate connection. The story begins when Braque visited Picasso’s studio to view Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), the painting that propelled cubism into the limelight (though it remained behind closed doors from 1907-1914). Picasso would not let anyone, not even his nearest and dearest see the painting. Only in 1914 did Picasso allow a circle of close friends, including Braque, to view the piece. Given the close relationship between the two artists, one would assume Braque was enthralled with Picasso’s latest masterpiece. Unfortunately, that was not the case. Braque was not only dismayed by the painting, but it made him want to “drink petrol and eat old rope.” Ouch. Not exactly a compliment that proves your buddy has your back. Even so, his statement must have made quite the first impression because from there their friendship caught fire and the two were nearly inseparable. These cubists in crime weren’t your typical bromance. They not only supported one another but constantly challenged and motivated each other to push their styles further.

Braque was the only artist throughout Picasso’s lifetime with whom he shared a deep, intimate connection. The story begins when Braque visited Picasso’s studio to view Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), the painting that propelled cubism into the limelight (though it remained behind closed doors from 1907-1914). Picasso would not let anyone, not even his nearest and dearest see the painting. Only in 1914 did Picasso allow a circle of close friends, including Braque, to view the piece. Given the close relationship between the two artists, one would assume Braque was enthralled with Picasso’s latest masterpiece. Unfortunately, that was not the case. Braque was not only dismayed by the painting, but it made him want to “drink petrol and eat old rope.” Ouch. Not exactly a compliment that proves your buddy has your back. Even so, his statement must have made quite the first impression because from there their friendship caught fire and the two were nearly inseparable. These cubists in crime weren’t your typical bromance. They not only supported one another but constantly challenged and motivated each other to push their styles further.

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Museum of Modern Art

In addition, these two certainly gave off soulmate vibes as their lives perfectly mirrored one another. Picasso was only born seven short months before Braque. Braque’s father was a house painter and decorator, while Picasso’s father was an academic painter. Both fathers strove to instill their profession into their sons. While Picasso was a womanizer, attention-grabbing, loud Spaniard, Braque shied away from the limelight and remained married to the same woman for the rest of his life. While Picasso was brash, Braque was diplomatic and soft-spoken, yet these two opposing forces complemented their partnership and helped shape art history in the twentieth century and beyond.  Picasso and Braque found inspiration in the work of Paul Cezanne and African art, particularly tribal masks, as the basis for cubism (appropriation, anyone?!). While Picasso shifted from narrative to pictorial imagery, Braque focused on his use of materials to manipulate light and space. For them, cubism touted the belief that nature was not to be mimicked but instead simplified, placing the focus on techniques of perspective, modeling, and foreshortening. In short, these cubists were all about flattening a painting to its basic form.

Picasso and Braque found inspiration in the work of Paul Cezanne and African art, particularly tribal masks, as the basis for cubism (appropriation, anyone?!). While Picasso shifted from narrative to pictorial imagery, Braque focused on his use of materials to manipulate light and space. For them, cubism touted the belief that nature was not to be mimicked but instead simplified, placing the focus on techniques of perspective, modeling, and foreshortening. In short, these cubists were all about flattening a painting to its basic form.

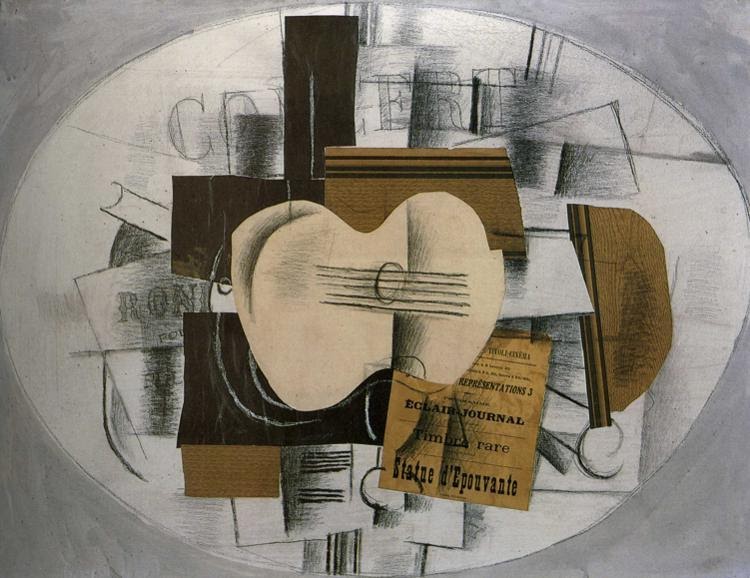

With the birth of cubism, two different sub-styles emerged. The first, analytical cubism, was popular with the dudes from 1908-12. Analytical cubism simplifies a painting into a severe series of planes and lines with a limited color palette. George Braque’s Still Life (Violin and Candles) (1910) is a good example of the artist experimenting with structural space within a two-dimensional frame. Picasso’s Violin (1912) is another example of this rigid cubist style.

Georges Braque, Still Life Violin and Candles, 1910

Pablo Picasso, Violin, Kroller-Muller Museum

The other more well-known type of cubism is synthetic cubism. Most cubist paintings we recognize today come from this second type that Picasso and Braque began to implement from 1912-14. In this type of cubism, the canvas is simplified, shapes are less extreme, and bright colors are used. Synthetic cubism saw the experimentation of collage and mixed-media materials such as newspaper or patterned paper were inputted into the canvas. Unlike analytical cubism, which flattened images and removed any trace of three-dimensional space, synthetic cubism added texture to the canvas, adding depth to an already square (ha! Get it?!) surface.

It was during this time that both Braque and Picasso began to experiment with papiers collés, which is French for pasted paper, using wood-grained paper that was then placed on white paper.

Georges Braque, Guitar and Program: Statue d'Epouvante, 1913

Braque and Picasso weren’t the only Cubies hanging about. Other artists such as Robert Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, and even Diego Rivera were influenced by cubism. Rivera’s The Cafe Terrace (1915) was created while the artist lived in Paris. It's not strictly a cubist painting, but you can see by the focus on geometric shapes in a very Picasso sort of fashion. Cubism and its influence were prominent in many of Rivera’s artwork from his time in The City of Light.

Diego Rivera, The Cafe Terrace (1915), Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cubism set geometric artistic expression on fire and the results can still be seen in contemporary works today. Bromances may not last forever, but this one surely had an impact on the world. Cubism was one of the first "isms" to get art nerds all hot and bothered, transforming the canon of art history into a period of abstraction that continues today.

Sources

- Abdu-Richman, Kelly, “9 Facts About ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,’” My Modern Met, accessed October 15, 2021, https://mymodernmet.com/les-demoiselles-davignon-facts/.

- “Analytical Cubism.” Tate. Accessed February 7, 2020. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/analytical-cubism.

- Brenson, Michael. Picasso and Braque, Brothers in Cubism. The New York Times. September 22, 1989. Accessed February 7, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/1989/09/22/arts/picasso-and-braque-brothers-in-….

- “Cubism.” Tate. Accessed February 7, 2020. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/cubism.

- “George Braque and Pablo Picasso.” MFA Masterworks Fine Arts Gallery. July 7, 2011. Accessed February 7, 2020. https://news.masterworksfineart.com/2017/07/11/georges-braque-and-pablo….

- “Papier-colle.” Tate. Accessed February 7, 2020. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/papier-colle.

- Rewald, Sabine. “Cubism.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2004. Accessed February 7, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cube/hd_cube.htm.

- Rivera, Diego. The Cafe Terrace. 1915. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/49.70.51/.

- Strickland, Carol. The Annotated Mona Lisa (New York City: John Boswell Management, Inc.), 138-139.

- “Synthetic Cubism.” Tate. Accessed February 7, 2020 https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/s/synthetic-cubism.

The cultural appropriation of African cultures by Picasso and his ilk for the sake of Cubism is not nearly discussed enough.