More about Portrait of a Young Girl

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

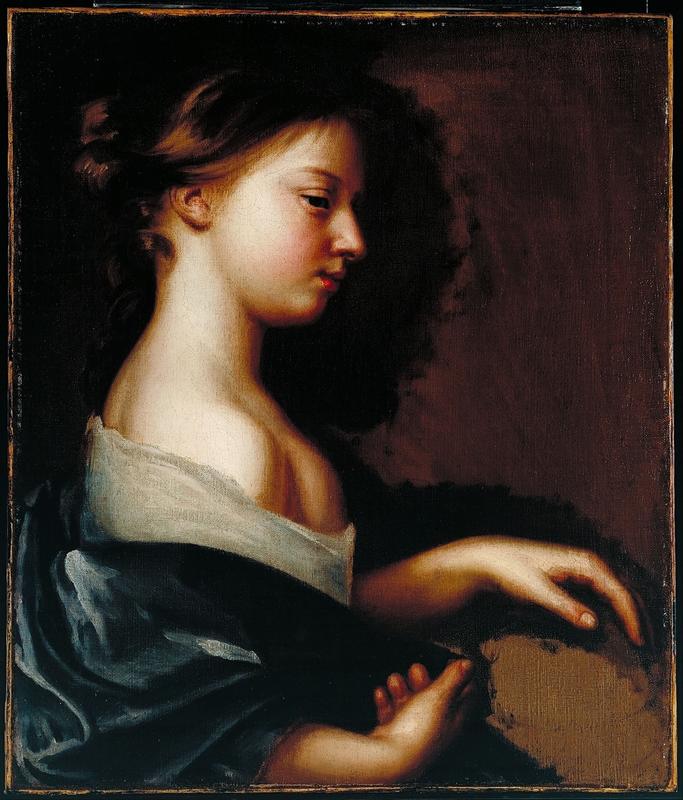

Mary Beale’s Portrait of a Young Girl is noted for its raw naturalness in comparison to Beale’s more formal portraits of dignitaries of the day.

Who would guess that behind this unassuming and sensitively rendered profile lies the story of a radical feminist marriage, a pioneering women’s artist collective, an intriguing mystery involving tragic romance, and ultimately a strange brush with an LSD-loving countess?

Thanks to the laboriously detailed journals of Mary’s husband, Charles Beale, we have a vivid picture of daily life in the Beale studio and household at the time Mary painted this in 1681. The Beales had a radical marriage for the time, in which Charles recognized his wife’s talent and gave up his own career ambitions to support her interests. This was not just a practical matter, but a way of life for the Beales, with Mary going so far as to write in her Essay on Friendship that wives should share “equal dignity and honour” with their husbands. For Charles, this included taking on traditionally feminine tasks like shopping for the children's clothes, as well as collaborating with Mary as a technician and colorist, and (luckily for researchers) recording every minute point of her process and activities.

From Charles’ journals, we know that this was likely part of a series of quick sketches and studies Mary was working on during that time in order to refine her skills and boost productivity. As such, it is an impulsive wet-into-wet sketch, likely done in a single sitting; less polished than her finished commissions but often regarded as among her best work for its natural human touch. We also know that Mary may have painted it on an onion sack, as Charles recorded she used this material and threads of coarse hemp or jute appear in the fiber of this canvas. Charles also leaves us titillating clues as to the identity of the mysterious girl in the portrait, so without further ado, let’s round up the usual suspects.

Suspect number one is Kate Trioche. Mary Beale appears to have believed not only in her own advancement as an artist at a time when that career was largely barred to women, but also in lifting other women up the ladder. Kate Trioche was one of several female studio assistants whom Mary trained and practiced with in what was essentially a salon for women painters and their male allies. The latter included celebrated court painter to King Charles II, Sir Peter Lely, an admirer and frequent collaborator of Mary’s who may have even had a hand in training her. We do not know precisely what became of Kate Trioche, but we do know that at least one girl whom Mary mentored, Sarah Curtis, went on to have a successful career and now has work hanging in the National Portrait Gallery. So, it’s possible Kate practiced professionally as well. In the spring of 1681, we know from Charles Beale’s diaries that Kate Trioche modeled for a nearly identical composition to this one, though that one was done on fine canvas. Furthermore, Mary used a Moll Trioche (presumably a relative of Kate) as the model for The Penitent Magdalene, and the sitters bear a noticeable resemblance.

Suspect number two is Alice Woodforde, who also served as a frequent model for Mary during this period and posed for a similar portrait. Alice was the Beales’ goddaughter, and daughter of Charles’ cousin, Alicia Beale Woodforde. Alicia married a friend and lodger of the Beales, the poet Reverend Samuel Woodforde, who wrote that they were, “in the opinion of all, I believe even our enemies, as happy and loving a pair as ever came together.” Tragedy cut wedded bliss short when Alicia died of childbirth complications only two years into the marriage. Mary and Charles took the motherless Alice under their wing whilst her father went into a period of deep mourning, alleviated only slightly by a portrait of his late wife by Peter Lely. Samuel wrote of a visit to Lely’s studio with Mary after his wife’s death, “I went…with cousin Beale…to Mr. Lely’s to sit for the finishing my dearest dearest [Alicia’s] picture…it is exceedingly like and by it I am able to perfectly remember her.” As the portrait was unfinished at the time of Alicia’s death, Mary posed for the hands on this occasion.

The last known suspect is Katy Sandys. Like Kate Trioche and Alice Woodforde, she was a regular presence in Mary Beale’s studio and often modeled for her in the spring of 1681. Information on Katy is sparse, but she is described as “...a small, blonde curly-haired girl.” She also posed for a series of sketches by Mary’s son, Charles Beale Jr., himself a noted portrait artist trained in his mother’s female-centric artistic salon.

The saga of the painting itself is no less compelling than that of its mysterious potential sitters. The piece disappeared from the historical record for nearly 300 years before a member of the aristocratic Feilding family purchased it from an antique shop in the 1970s. The Feildings spawn from an ancient Habsburg line remarkable for its plethora of beheadings, or as the current heiress, Amanda Feilding, Countess of Wemyss prefers to put it, “rather nice anti-establishment personalities.” The Tate acquired it from the estate of Amanda’s mother, Margaret Feilding in 1992. Margaret was a Catholic philanthropist who lived in genteel poverty in a Tudor castle (and Harry Potter filming location) with her amateur artist husband, Basil, who farmed by night so he could paint by day.

Amanda has taken the Feilding bohemian streak a bit farther. In her youth, she left a convent school to hitchhike from Britain to Sri Lanka to study mysticism with her renegade godfather who had become a Buddhist monk, but got only as far as Syria before taking up with a tribe of drunk Bedouins to party in the desert instead. Her other exploits include drilling a hole in her own skull and filming it for an underground art film, and fiercely advocating for the use of LSD to treat mental illness. Today, her stately home of Beckley Park, whose walls Portrait of a Young Girl once graced, serves as the headquarters of her psychedelic research foundation.

Sources

- Barber, Tabitha. “Summary: Portrait of a Young Girl.” Tate. May, 2001. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/beale-portrait-of-a-young-girl-t06…

- Barber, Tabitha. “Catalogue entry: Portrait of a Young Girl.” Tate. July, 2006. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/beale-portrait-of-a-young-girl-t06…

- Butt, Stephen. “Mary Beale and her family.” The Woodforde Story. Accessed January 15, 2022. https://www.woodforde.org/mary-beale/

- Draper, Helen. “ ‘Her Painting of Apricots’: The Invisibility of Mary Beale (1633-1699).” Forum for Modern Language Studies, Volume 48, Issue 4, October 2012, Pages 389–405. https://doi.org/10.1093/fmls/cqs023

- Grosvenor, Bendor Grosvenor. “Where are the women in art?” Art History News, May 21, 2014. https://www.arthistorynews.com/articles/2802_Where_are_the_women_in_art…

- Jones, Rica and Joyce H. Townsend, “Essay: Portrait of a Young Girl c. 1681 by Mary Beale,” Tate, August, 2005. https://www.tate.org.uk/about-us/projects/tudor-stuart-technical-resear…

- Miller, Lydia. “The Two Marys of St James’s Church, Piccadilly.” Philip Mould & Company. Accessed January 15, 2022. https://philipmould.com/news/131-the-two-marys-of-st-jamess-church-picc…

- “Sarah Hoadlly.” National Portrait Gallery. Accessed January 15, 2022. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp07112/sarah-hoadly

- Simon, Matt. “Inside the Mind of Amanda Feilding, Countess of Psychedelic Science.” Wired, February 15, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/inside-the-mind-of-amanda-feilding-countess…

- “Sir Peter Lely: Portrait of Alice Woodforde (nee Beale).” Sotheby’s. Accessed January 15, 2022. https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2009/important-old-mast…

- Smith, Mark. “Amanda Feilding: Has this ‘mad’ hedonistic hippie been proved right 50 years on?” You Magazine, May 2, 2021. https://www.you.co.uk/amanda-feilding-interview/