More about Mariana

- All

- Info

- Shop

Editor

A Medieval maiden yearning for death? Classic Millais.

Like fellow Pre-Raphaelite WIlliam Holman Hunt’s painting Claudio and Isabella, Millais’ Mariana depicts a character from Shakespeare’s “Measure for Measure.” Though to be more precise, the subject of this painting is actually derived from an 1830 poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson called “Mariana,” which was itself derived from the Shakespeare play. The story goes that Mariana was betrothed to Lord Angelo before he became the temporary ruler of Vienna. When Mariana loses both her brother and her dowry in a shipwreck, Angelo abandons ship as well, ending the engagement and condemning her to a lonely life in a secluded moated grange. Angelo turns out to be one of Shakespeare’s nastier villains, so why on earth she continues to pine after him beats me, but pine she does. The following verse from Tennyson’s poem, which describes Mariana’s growing misery as time passes, accompanied Millais’ painting at its first exhibition in 1851:

She only said, 'My life is dreary,

He cometh not,' she said;

She said, 'I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!'

Many details of the painting allude to time passing and her longing for death. The afternoon sunlight pouring onto her long-labored-over embroidery and her back-cracking stretch indicate the repetitiveness of her life. The leaves that litter her floor and work table evoke decay as she gazes disconsolately at the autumnal trees outside her window. Even the stained glass, which was partly copied from Merton College Chapel and partly of Millais’ own invention, bears a Latin motto meaning “In heaven there is rest.” The annunciation scene in the window contrasts directly to Mariana’s unfulfillment, while the bed and burning candle suggest physical desire. These details show how innovatively Millais uses objects; while fellow Pre-Raphaelite Rossetti preferred one-to-one symbolism, à la “dove = Christ”, Millais has a more well-rounded approach, allowing objects to have their own natural presence while still evoking Mariana’s psychological state.

The Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood had been formed by English artists Millais, Rossetti and William Holman Hunt in 1848 as a reaction against what they considered the frivolity and staleness of the Academy, where they were students. They turned to the art of the past, from before Academy fave Raphael came along and ruined everything, for inspiration. There they found the attention to realism, as well as a certain sense of probity, that appealed to them. The rebels favored rich jewel tones, finely wrought details, faithfulness to nature, and serious, literary subjects, all of which are on display in Mariana. Shakespeare’s maidens were a common choice for the PRB, Millais’ most famous work probably being his painting of Ophelia, but his addition here of Romantic poetry was rather a novelty. In fact, in 1850 when Tennyson heard that Millais had done a painting of a poem by Coventry Patmore, he is noted to have wished aloud that Millais would paint one of his own poems. Little did he know, Mariana was already in the works.

One painting that made a big impression on the young Pre-Raphaelites was the Arnolfini Portrait by Jan Van Eyck, which was purchased by the National Gallery in 1842. At the time, the National Gallery and Royal Academy shared the same building, and the Arnolfini Portrait was just down the hall from where Millais and his buds were studying. Van Eyck’s portrayal of secular subject matter (in this case, likely a wedding) imbued with religious meaning, as well as his work’s durability, detail, and glossy finish, inspired the PRB, and especially Millais, who loved Medieval manuscripts and the bejeweled colors of the Northern Renaissance. For Mariana, he borrows Van Eyck’s rich colors and delicate precision, so fine that each one of Mariana’s eyelashes is distinctly delineated. Further echoes from the Arnolfini Portrait can be see in the placement of the windows, the rich deep tones of Mariana's dress, the voluptuousness of her figure, the wooden plank floor, the curtained bed, and the single burning candle. These references to a wedding portrait make the solitary Mariana seem all the more lonely and unfulfilled. While Millais does not incorporate a dog like in the Arnolfini Portrait, he does include the mouse mentioned in Tennyson’s poem, which he painted after a dead model. (Which I know sounds weird, but you try getting a mouse to sit still.)

Millais showed this painting, alongside two others, at the Academy’s exhibition in 1851, just one year after his disastrous showing of Christ in the House of His Parents. This time his reception was a teensie bit warmer, and as the decade wore on, he painted more lone maidens and tragic lovers because they were better received than his religious imagery. It’s easy to see why an image like Mariana would be popular--the solitary woman waiting for her prince to appear would resonate with Victorian ideology about the role of women--demure, domestic, and enduring suffering with patience. It was in the wake of the exhibition of 1851 that Ruskin wrote a glowing review of the Pre-Raphaelites. Shortly after, Ruskin invited Millais up to Scotland to paint his portrait and Millais showed Ruskin his gratitude by up and stealing his wife. In 1853, Millais was elected an associate of the Royal Academy, so he was seen as a bit of a traitor by the Pre-Raphaelites, too. Millais was so talented, though, that any ill feelings toward him were likely a classic case of “they hate you ’cuz they ain’t you.”

This work was purchased by dealer Henry Farmer, who had also bought Christ in the House of his Parents, and he in turn sold it to one Benjamin Godfrey Windus, a retired coach builder and purveyor of “Godfrey’s Cordial,” a popular children’s throat medicine. He was a prominent collector of the Pre-Raphaelites and Turner, clearly possessing an eye for the most groundbreaking British art of his century.

Sources

- Fowler, Frances. “‘Mariana,’ Sir John Everett Millais, 1851 | Tate” last modified December 2000. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millais-mariana-t07553.

- Hilton, Timothy. The Pre-Raphaelites. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1970.

- Marsh, Jan. Pre-Raphaelite Women: Images of Femininity. New York: Harmony Books, 1987.

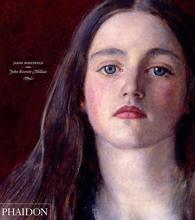

- Rosenfeld, Jason. John Everett Millais. London: Phaidon Press, 2012.

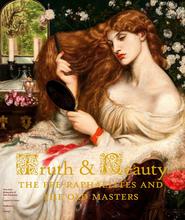

- Smith, Alison. Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites. London: The National Gallery, 2017.

- Treuherz, Julian. Victorian Painting. London: Thames & Hudson, 1993.

Featured Books & Academic Sources

The following is the poem "Mariana" by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, first published in "Poems, Chiefly Lyrical" in 1830:

"Mariana in the Moated Grange"

(Shakespeare, Measure for Measure)

With blackest moss the flower-plots

Were thickly crusted, one and all:

The rusted nails fell from the knots

That held the pear to the gable-wall.

The broken sheds look'd sad and strange:

Unlifted was the clinking latch;

Weeded and worn the ancient thatch

Upon the lonely moated grange.

She only said, "My life is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

Her tears fell with the dews at even;

Her tears fell ere the dews were dried;

She could not look on the sweet heaven,

Either at morn or eventide.

After the flitting of the bats,

When thickest dark did trance the sky,

She drew her casement-curtain by,

And glanced athwart the glooming flats.

She only said, "The night is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

Upon the middle of the night,

Waking she heard the night-fowl crow:

The cock sung out an hour ere light:

From the dark fen the oxen's low

Came to her: without hope of change,

In sleep she seem'd to walk forlorn,

Till cold winds woke the gray-eyed morn

About the lonely moated grange.

She only said, "The day is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

About a stone-cast from the wall

A sluice with blacken'd waters slept,

And o'er it many, round and small,

The cluster'd marish-mosses crept.

Hard by a poplar shook alway,

All silver-green with gnarled bark:

For leagues no other tree did mark

The level waste, the rounding gray.

She only said, "My life is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said "I am aweary, aweary

I would that I were dead!"

And ever when the moon was low,

And the shrill winds were up and away,

In the white curtain, to and fro,

She saw the gusty shadow sway.

But when the moon was very low

And wild winds bound within their cell,

The shadow of the poplar fell

Upon her bed, across her brow.

She only said, "The night is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

All day within the dreamy house,

The doors upon their hinges creak'd;

The blue fly sung in the pane; the mouse

Behind the mouldering wainscot shriek'd,

Or from the crevice peer'd about.

Old faces glimmer'd thro' the doors

Old footsteps trod the upper floors,

Old voices called her from without.

She only said, "My life is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

The sparrow's chirrup on the roof,

The slow clock ticking, and the sound

Which to the wooing wind aloof

The poplar made, did all confound

Her sense; but most she loathed the hour

When the thick-moted sunbeam lay

Athwart the chambers, and the day

Was sloping toward his western bower.

Then said she, "I am very dreary,

He will not come," she said;

She wept, "I am aweary, aweary,

Oh God, that I were dead!"

Sources

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson. "Mariana." Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45365/mariana. Accessed March 20, 2019.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Mariana (Millais)

Mariana is an 1851 oil-on-panel painting by John Everett Millais. The image depicts the solitary Mariana from William Shakespeare's Measure for Measure, as retold in Tennyson's 1830 poem "Mariana". The painting is regarded as an example of Millais's "precision, attention to detail, and stellar ability as a colorist". It has been held by Tate Britain since 1999.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Mariana (Millais)