More about Judy Chicago

- All

- Info

- Video

- Shop

Works by Judy Chicago

Contributor

Judy Chicago, born יהודית כהן, Judith Cohen, in 1939 to a family of rabbis and rebbetzins, is a premier authority in art, feminist art, and art education, just as her ancestor the Vilna Gaon was the premier authority in the yeshiva tradition.

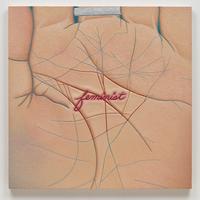

In a 1974 interview, Chicago described the goal of her groundbreaking work as an educator, introducing the field of women's art history in the process of, "moving away from the male-dominated art scene and being in an all-female environment where we could study our history separate from men’s and see ourselves in terms of our own needs and desires, not in terms of male stereotypes of women."

In this sense Chicago operationalized the insights of the feminist movement by creating a sort of art yeshiva for women, in the sense that the Vilna Gaon was the first to make it possible for Jewish men to study Torah as a full-time occupation with material support: Chicago was demonstrating to her students that they did not need the material assistance or guidance of any kind from men in order to impress an authentic artistic signature on the world.

Chicago was showing a feminist position that was strategically oriented toward separating women's history and creating a new, pure environment where women could examine and interpret art, including the largely-male "canon," as well as their own work, without the observation, judgment or participation of men. This is politically significant in a parallel way to the speeches of the early post-Hajj Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey: both Black leaders brought forward a "separatist" Black nationalist position which was both controversial and strategic, in order to create an autonomous system, or the idea, image and threat of an autonomous system, outside of the frame of white male "support" and control.

The criticism that Chicago and other early non-Black feminists could not finally refute was that these were almost entirely self-identified white women's issues, driven by an agenda that viewed, at least implicitly, gender, race, sexuality, ethnicity and culture as separable domains, to the detriment of those who were not able to identify as white and who are otherwise different from the norm of representation. These criticisms are especially available in the work of Audre Lorde, bell hooks, and, in a less direct but equally relevant form, Octavia Butler and Toni Morrison. As with the development of any political movement, the tension of debate and disagreement would ideally drive the movement toward acknowledging its own lacunae.

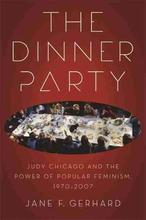

The process of encouraging a convivial environment between women and showing femininity as an aspect of a heritage with an inspired history, as Chicago did in her great work The Dinner Party, upended conventions of feminism by encouraging a view of femininity and womanhood as positive values in and of themselves with particular hermeneutic and even spiritual insights, rather than simply as pathological symptoms of injustice.

On a September 1975 book tour, Warhol drew male and female reproductive organs as autographs in copies of his book. As Judith Gerowitz, Chicago had done this kind of artwork in the early 1960's, which means that probably during that decade, Warhol saw her work, or heard about it, and hid her influence.

This is one aspect of the cultural environment that compelled Chicago to coin the term "feminist art education" in the 1970's, in order to make it unnecessary to don "male drag" in order to make a living. Chicago dedicated herself to making opportunities for women to make art without having to separate their gender from the formal content.

Sources

- Bloch, Avital and Lauri Umansky. Impossible to Hold: Women and Culture in the 1960's. New York: NYU Press, 2005.

- Colacello, Bob. Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up. New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

- Gerhard, Jane. "Judy Chicago and the Practice of 1970's Feminism." Feminist Studies 37, no. 3 (Fall 2011): 591-618.

- "Judy Chicago and Lloyd Hamrol Interview Each other.” Criteria: A Review of the Arts 1, no. 2 (November 1974).

- Keifer-Boyd, Karen. "From Content to Form: Judy Chicago's Pedagogy with Reflections by Judy Chicago." Studies in Art Education 48, no. 2 (Winter 2007): 134-154.

Contributor

Judy Chicago is a paramount figure in feminist art.

She wore boots and smoked cigars like the dudes in her UCLA classes. Later on, she decided that being a woman was something she couldn’t ignore in her art.

A gallery owner nicknamed her Judy “Chicago” because of her accent. Before that she had last names like Cohen from her dad’s family and Gerowitz from her late husband. She supposedly chose Chicago over all the other names (names she’d gotten from men…feminism has arrived) and for an exhibition ad in Artforum she stood in a boxing ring, wearing a sweatshirt inscribed with the name Judy Chicago.

Chicago, along with Miriam Schapiro (fellow feminist), created a feminist performance and installation exhibit entitled Womanhouse in 1972. The space was a soon-to-be demolished little house in the seedier section of Hollywood. Chicago’s own installation in the show was called Menstruation Bathroom. Pretty self-explanatory – picture a trashcan full of used tampons. Yum. After that, she became famous for her vulvic array in The Dinner Party.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Judy Chicago

Judy Chicago (born Judith Sylvia Cohen; July 20, 1939) is an American feminist artist, art educator, and writer known for her large collaborative art installation pieces about birth and creation images, which examine the role of women in history and culture. During the 1970s, Chicago founded the first feminist art program in the United States at California State University, Fresno (formerly Fresno State College) which acted as a catalyst for feminist art and art education during the 1970s. Her inclusion in hundreds of publications in various areas of the world showcases her influence in the worldwide art community. Additionally, many of her books have been published in other countries, making her work more accessible to international readers. Chicago's work incorporates a variety of artistic skills, such as needlework, counterbalanced with skills such as welding and pyrotechnics. Chicago's most well known work is The Dinner Party, which is permanently installed in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum. The Dinner Party celebrates the accomplishments of women throughout history and is widely regarded as the first epic feminist artwork. Other notable art projects by Chicago include International Honor Quilt, Birth Project, Powerplay, and The Holocaust Project. She is represented by Jessica Silverman gallery.

Chicago was included in Time magazine's "100 Most Influential People of 2018".

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Judy Chicago