More about Self-Portrait as a Lute Player

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

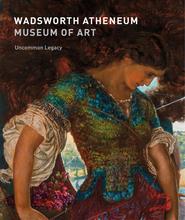

Artemisia Gentileschi's Self portrait with Lute, since its "public debut" at Sotheby's in 1998, has carried the title Self Portrait as a Lute Player (Autoritratto come suonatrice di liuto).

In 2014, the Wadsworth Atheneum paid more than $3 million for this painting. Blogger Alain R. Truong publishes sources linking the work to the years 1616-17, during Artemisia's time in Firenze, based on the Florentine luxuriousness of Artemisia's gold-embroidered outfit, complete with a high-quality turban and sash. Scholars suggest that Artemisia did this work on commission for the Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici, as it is listed in a 1638 inventory of the Villa Medici of Artimino. There's no word yet as to how, exactly, a major work by the great Artemisia could escape curatorial and critical notice for 360 years. Despite Artemisia's fame and success during her lifetime, nobody bothered to dedicate a real monograph to her until Mary Garrard's 1989 work, which exposes much of the centuries-old habit among historians to misattribute women's artworks to male artists.

For critic-biographers and curators, the low-cut bodice of this Autoritratto can present a dilemma regarding Artemisia's so-called "moral reputation," the focus on which is just another way of attacking the artist for her original sin of having been born female. For all we know about the work and her early married life, the bodice is to facilitate breastfeeding, and the irony of the work, from the artist's perspective, would be the tension between her domestic and professional life. We know that one of Artemisia's children, a painter named Prudentia ("Prudence"), survived, and she was born right around the same time as the release of this work, so this explanation seems likely.

Original letters in Artemisia's hand demonstrate that she didn't take no guff from nobody, but she managed to coat her necessarily firm and protective demeanor with a thick pastel candy coating in order to avoid raising the hackles of her tender-egoed, aristocratic patrons. Over three decades after this work, when in her mid-to-late fifties, Artemisia begins a letter to a patron with the mid-seventeenth-century equivalent of "this isn't a secure line": "In case the gentleman carrying this letter decides to read it, I prefer not to discuss our business." In order to do a painting for you, I'm gonna need a deposit, she reminds him, before begging him, for the sake of the Almighty, to pay her the price she asked if he wants a work of decent quality. "I swear, as your servant, that I would not even give it to my father for the price I gave you." In one of the most dramatic sign-offs possible, Artemisia reassures "His Most Illustrious Lordship" that he will "suffer no loss" investing in her, and that he'd be sure to find "the spirit of Caesar in the soul of a woman (ritrovera uno animo di Cesare nell’anima duna donna)"! Luckily, the spirit of Brutus wasn't incarnated anywhere near Artemisia.

Sources

- Archivio di Stato, Florence. Guardaroba Medicea 532, Inventario della Villa di Artimino 1638, fol. 16v.

- "Autoritratto come suonatrice di liuto," Finestre sull'Arte, Mar. 21, 2016, https://www.finestresullarte.info/operadelgiorno/2016/493-artemisia-gen….

- DeLamotte, Eugenia C., Natania Meeker, and Jean F. O'Barr. Women Imagine Change: A Global Anthology of Women's Resistance from 600 B.C.E. to Present. New York: Psychology Press, 1997.

- Garrard, Mary D. Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Greenberger, Alex. "Artemisia Gentileschi Made History with 17th-Century Feminist Art…" ARTnews, Apr. 6, 2020, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/artemisia-gentileschi-most-fam….

- Jullion, Marie-Christine, Clara Bulfoni, and Virginia Sica. Al di là del cliché: rappresentazioni multiculturali e transgeografiche del femminile. Milano: FrancoAngeli, 2012.

- Truong, Alain R. "Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as a Lute Player." Alain Truong, Jan. 10, 2014, http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2014/01/10/28914929.html.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Self-Portrait as a Lute Player

Self-Portrait as a Lute Player is one of many self-portrait paintings made by the Italian baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi. It was created between 1615 and 1617 for the Medici family in Florence. Today, it hangs in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, US. It shows the artist posing as a lute player looking directly at the audience. The painting has symbolism in the headscarf and outfit that portray Gentileschi in a costume that resembles a Romani woman. Self-Portrait as a Lute Player has been interpreted as Gentileschi portraying herself as a knowledgeable musician, a self portrayal as a prostitute, and as a fictive expression of one aspect of her identity.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Self-Portrait as a Lute Player