More about Jean-Baptiste Belley, Deputy of Santo Domingo

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

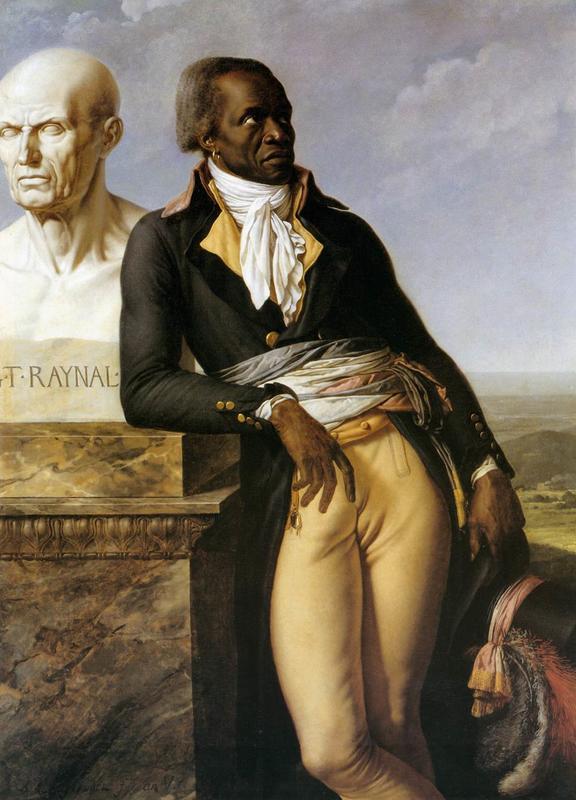

Girodet’s portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley was the first painting of a black official in Western art.

This portrait worked within the tradition of portraiture of powerful figures at the time, and followed in the neo-classical footsteps of Girodet’s teacher, Jean- Jacques David, making the painting pretty revolutionary.

But let’s not forget what this painting is really all about. Meet Jean-Baptiste Belley, the Deputy of Saint Domingue and general badass. Born in Senegal and taken to the French colonies by the slave trade, Belley was enslaved until he bought his freedom after serving in the French army. About his emancipation he said that ,“Through painful work and sweat, conquered a liberty [he] had honorably enjoyed...while cherishing [his] fatherland."

Living free in Saint Domingue, Belley fought alongside both enslaved and other free black people in the Haitian revolution when it started in 1791, and was injured a handful of times. Haiti’s revolt was part of a string of slave rebellions in the Caribbean colonies which eventually led to slavery’s abolition in the colonies in 1794. Due to the nature of the French government, the declaration had to be approved back in France, and Belley was nominated as one of the anti-slavery representatives from the colonies. He was the first black deputy to serve.

It would be difficult to argue this portrait was apolitical. Closely following the abolition of slavery in the colonies, this traditionally styled portrait features a leader of the Haitian rebellion and the first black delegate of the National Convention. Belley is painted with some of the traditional elements of a political portrait- mainly, it’s about ¾ length and the only architecture is a giant classical marble bust. The bust actually portrays abolitionist Guillaume Thomas Francois Raynal (say that 10 times fast). His serious countenance reflects his station, and the reading glass tied to his belt communicates to the viewer that this man is educated and literate.

On top of that, he’s cute and wearing a patriotic 'fit. Wearing the traditional ruffly shirt, britches and coat look that we’ve all come to love from period romances, he looks v put together. You can see his feathers, sash, and hat wrap are color coordinated with each other and with the French flag which is red, white, and blue. A man after my own heart, he’s rocking hoops, a clear reference to his unique heritage as a Sengelese-Caribbean man, and he’s wearing a soldier’s uniform. He looks off in the distance, and behind him is Saint Domingue, his place of residence.

Belley is purposefully being portrayed as a Frenchman. Which of course, he was. He was stolen from Senegal as a child, lived in the French colonies, lived in a French colony, spoke French, fought in the French army for 25 years, and eventually worked in the French government. But France was just coming to terms with its new population and the consequences of its horrible enslavement and colonization policies. Belley, painted in all his patriotic glory, is serving as a symbol for the bright future of the Republic.

Though of course, it’s not that simple. When the crap hit the fan due to bloodthirsty wig burners tearing it all down and causing financial instability, French officials began to rethink their new position on slavery. This 1797 portrait was painted in the midst of much racial tension after a ruling that black people working in the republic were citizens, and a surge of pro-slavery and anti-black attitudes ensued. As pro-slavery rhetoric increased, so did the ciruclation of racist science, language, and violence.

While many agree that Girodet’s intention was to portray Belley nobly, as a white man it seems he was unable to portray Belley without falling into some stereotypes. Specifically, that D is poppin. The bulge in his pants and the way his finger gestures to it is a clear break from tradition in portraying male bodies, and also exemplifies the racist sexualization of black men at the time. Belley died in 1805, after spending 3 years in a French prison. He ended up there when a post- Haitian revolution decree from Napoleon was sent to Saint Domingue to kill every black man who had worn a French soldier’s uniform.

So when we look at portraits like this, of strong badass people with their own personal histories, we cannot ignore their cultural contexts, nor the personal failings of their painters (and governments).

Sources

- Bellhouse, Mary L. "Candide Shoots the Monkey Lovers." Political Theory 34, no. 6 (December 2006): 741-84. doi:10.1177/0090591706293020.

- Collins, Megan Marie. "The Portrait of Citizen Jean-Baptiste Belley, Ex-Representative of the Colonies by Anne-Louis Girodet Trioson: Hybridity, History Painting, and the Grand Tour." Master's thesis, Brigham Young University, 2006.

- Fumaroli, Marc, and Bruno Chenique. Girodet, 1767-1824. Edited by Sylvain Bellenger. Paris: Gallimard, 2006.

- "Jean-Baptiste Belley." The Art Institute of Chicago. Accessed July 15, 2019. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/44272/jean-baptiste-belley.