More about A Centennial of Independence

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

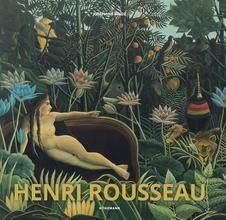

Henri Rousseau never would have believed that major institutions and art critics would hail him as a genius of modern art just a few decades after his death.

After all, the jurors of the official Paris Salons repeatedly rejected his artworks. But what was a lowly toll collector to do? Before giving up his day job in 1893, Rousseau was just another cog in the bureaucratic machine. Little did he know, his humble beginnings would earn him the nickname of Le Douanier, French for “the customs agent,” and he would be hanging out with conceited geniuses like Picasso in no time, even if they couldn’t even be bothered to call him something that actually referred to his previous job.

But perhaps it was Rousseau’s humble beginnings that helped him connect with the zeitgeist of the late-nineteenth-century France. In 1892, he stopped imagining jungle scenes to commemorate the one-hundredth anniversary of the first French Republic – the common people’s first and most significant triumph over monarchy during the French Revolution. Even after Napoleon tried to dismantle the Republic and install himself as another emperor, the French people fiercely fought back in the name of democracy and remain extremely proud of this period in their history.

When Rousseau painted this celebratory image of peace under democracy, the Third Republic was in full swing, and the French people had finally gotten the peaceful, democratic government they deserved. Although they look stereotypically stuffy and old-school, the men on the right wearing suits and white wigs are actually symbols of the stable Republic that prevailed at the time. The dancing peasants are celebrating this era of good and fair government. Rousseau’s child-like artwork is so obvious sometimes that I’m surprised there isn’t a sun in the upper-left corner smiling and wearing sunglasses. More subtly, Rousseau’s bright palette also communicates this moment of political content.

But people liked Rousseau’s straightforward style. Of course, Rousseau would not have been noticed without a little help from his more successful friends. The self-taught artist owed special thanks to a certain German art collector named Wilhelm Uhde, who owned this painting by 1910. Before the outbreak of World War I, Uhde was a flourishing art collector in Paris. During his prime, he befriended Picasso and ran in the same circles as Gertrude Stein. He had a shrewd eye for art and particularly liked the work of Rousseau. In 1909, just one year before the artist’s death, Uhde arranged Rousseau’s first solo show in his gallery, which doubled as a Paris furniture shop. Not very glamorous, but I guess beggars like Rousseau couldn’t be choosers.

In the next few years, A Centennial of Independence was displayed at the infamous 1913 Armory Show, where modern, European art debuted in the United States. Sadly, Rousseau died three years before seeing his art go international. American audiences loved the style and content of Rousseau’s naive works. They especially jived with the subject matter of celebrating independence from tyrannical monarchy, which we might want to start thinking about again nowadays.

Sources

- Arnason, H.H. and Elizabeth C. Mansfield. History of Modern Art. 7th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc., 2013.

- Nechvatal, Joseph. “In the Jungle of Henri Rousseau’s Imagination.” Hyperallergic. https://hyperallergic.com/308200/in-the-jungle-of-henri-rousseaus-imagi…. Accessed November 20, 2018.

- New-York Historical Society Museum & Library. “A Centennial of Independence.” The Armory Show at 100. http://armory.nyhistory.org/a-centennial-of-independence/. Accessed November 20, 2018.

- Nykolak, Jenevieve. “Henri Julien Félix Rousseau.” Outliers and American Vanguard Artist Biographies. Exhibitions. https://www.nga.gov/features/exhibitions/outliers-and-american-vanguard…. Accessed Januar

- Phaidon. “The amazing life story of Wilhelm Uhde.” News. March 17, 2015. https://www.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2015/march/17/the-amazing-l…. Accessed November 20, 2018.

- The Art Story. “Henri Rousseau.” Artists. https://www.theartstory.org/artist-rousseau-henri.htm. Accessed January 21, 2019.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Third Republic, French History.” https://www.britannica.com/topic/Third-Republic-French-history. Accessed January 21, 2019.

- The J. Paul Getty Trust. “A Centennial of Independence.” Collection. http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/816/henri-rousseau-a-centen…. Accessed November 20, 2018.

- The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. “Henri Rousseau.” Artists. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/henri-rousseau. Accessed November 20, 2018.