More about Newton

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

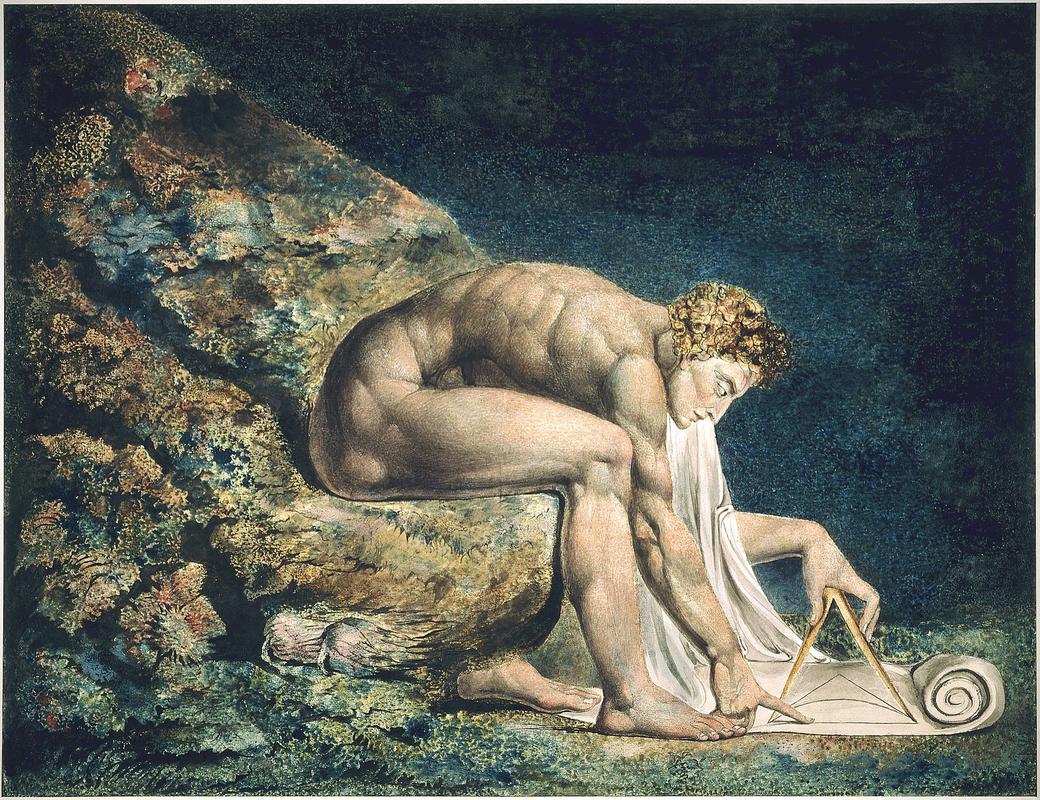

Newton is like William Blake’s version of that Facebook photo where you’re flipping the camera off and sticking your tongue out and have dead eyes and somebody keeps retagging you.

In Blake’s own words “art is the tree of life, science is the tree of death.” Which is almost as dramatic as his description of the “Water-wheels of Newton” as “cogs tyrannic.” But Blake really liked imagination, so the stuffy gentlemen scientists of Enlightenment Britain were Blake’s least favorite kind of person and so maybe we can forgive the scathing generalization that scientists are so obsessed with twirling their compasses on paper that they forget to look at all the trippy stuff nature has going on that weird hill that always seems to be right behind them.

Really, Blake was more Summer of Love ’69 than “burn the astrophysicist.” He didn’t get along well with authoritative educators and ended up getting most of his education through spirit mediums. His dead brother Robert gave him art lessons while Blake dreamt, and he had a childhood habit of predicting whom would hang from the gallows (a charming boy, surely). He and his wife liked to lay naked in their yard, reciting poetry as Adam and Eve in a kind of bible foreplay. Blake was a hippie right down to the violent pacifism. He was once arrested on charges of assaulting a soldier and yelling: “Damn the king. The soldiers are all slaves.”

Unlike the fashionable rebels of the 18th century, Blake was a real activist. He illustrated and wrote against the value of female chastity, authoritarian rule, slavery, and one time he joined a mob that ended up burning a prison to the ground. Despite being an antisocial SJW with a habit of seeing angels hiding in trees, Blake had super low self-esteem. He prefaced his marriage proposal to Catherine Boucher with the question “Do you pity me?” His lack of confidence might be traced to being bullied by school children while drawing the Westminster Abbey as a young man. The pity party went beyond his marriage. Most of the artwork that Blake sold during his lifetime was on commissions from friends that knew how broke he was. Thomas Butts bought many of his important works the way that a parent buys their child’s art from a middle school art show. Butts’ descendants spent the next hundred years getting rid of Blake’s art to make space on their walls.

Blake spent most of his time in his room, working in seclusion, and scribbling angsty lyrics like, “corporeal friends are spiritual enemies” in his poetry. But his reputation as an artist began growing late in his life and after he died. John Ruskin called Blake as “magnificent and mighty” as Turner and said that “In expressing conditions of glaring and flickering light, Blake is greater than Rembrandt.” Still, Blake never escaped his reputation as an 18th century, hippie weirdo. Ruskin said also that Blake was “sincere, but…somewhat diseased in brain.” As such nobody took his pointed critique of Newton very seriously. He was voted 38th most important Briton of all time, which is higher than King Arthur but a good 32 places lower than his science-y, would-be adversary Sir Isaac Newton. Losing a popularity contest to a nerd probably isn’t doing his self-esteem any favors.

Sources

- “Biography: William Blake.” The Poetry Foundation Website, accessed May 8, 2017. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/william-b…

- Blake, William. “Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion.” The Preterist Archive, October 2011. Accessed May 8, 2017. https://www.preteristarchive.com/Books/1804_blake_jerusalem.html

- Blake William. “Visions of the Daughters of Albion.” The Poetical Works of William Blake. Edited by John Sampson. New York: Oxford University Press, 1908. Accessed May 8, 2017. http://www.bartleby.com/235/256.html

- Blake, William. “The French Revolution.” The Poetical Works of William Blake. Edited by John Sampson. New York: Oxford University Press, 1908. Accessed May 8, 2017. http://www.bartleby.com/235/254.html

- Cook, E.T. and Alexander Wedderburn. “A Manuscript Discussion of William Blake omitted from the published version – a note to Chapter VII “The Lamp of Obedience.” The Victorian Web. Accessed May 8, 2017. http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/ruskin/7lamps/c

- Blake, William. “Milton.” The Prophetic Books of William Blake. Edited by Archibald G.B. Russel and E.R.D. Maclagan. London: Cheswick Press, 1907. Accessed May 8, 2017. https://www.archive.org/stream/propheticbooksof00blak/prophetic booksof00blak_djvu.txt

- Galvin, Rachel. “William Blake: Visions and Verses.” Humanities, May/June 2004, Vol. 25 No. 3. Accessed May 8, 2017. https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2004/may june/feature/william-blake-visions-and-verses

- “The Gothic Life of William Blake: 1757 – 1827.” Lilith eZine, accessed May 8, 2017. http://www.lilith-ezine.com/articles/williamblake1.html

- Editors William Blake Archive. “John Gabriel Steadman, Narrative, of a Five Years’ Expedition, Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (Composed 1796).” The William Blake Archive, accessed May 8, 2017. http://www.blakearchive.org/ work/bb499

- Livio, Mario. December 23, 2014. “On William Blake’s ‘Newton.’” Huffington Post, accessed May 8, 2017. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mario-livio/on- william-blakes-newton_b_6036258.html

- Mitchell, Paul. December 1, 2000. “William Blake: A radical visionary.” World Socialist Website, accessed May 8, 2017. https://www.wsws.org/en/arti cles/2000/12/blak-d01.html

- Tatham, Frederick. The Letters of William Blake: Together With a Life. Edited by Archibald G. B. Russell. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Library, 2005. Accessed May 8, 2017. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/g/genpub/ACA46 92.0001.001?view=toc

- “The Top 100 Great Britons.” Internet Archive: Wayback Machine, December 4, 2002. Accessed May 8, 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/2002120421 4727/http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/programmes/greatbritons/list.shtml/

- “The Final Top Ten.” Internet Archive: Wayback Machine, December 4, 2002. Accessed May 8, 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20021204212902/ht tp://www.bbc.co.uk:80/history/programmes/greatbritons/final_topten.shtml

- Ruskin, John. Works of John Ruskin, Volume 15. Edited by E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1904. Accessed May 8, 2017. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=nEg8ULbzEJcC&rdid =book-nEg8ULbzEJcC&rdot=1

- “William Blake Biography.” William-Blake.org, accessed May 8, 2017. http://www.william-blake.org/biography.html

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Newton (Blake)

Newton is a monotype by the English poet, painter and printmaker William Blake first completed in 1795, but reworked and reprinted in 1805. It is one of the 12 "Large Colour Prints" or "Large Colour Printed Drawings" created between 1795 and 1805, which also include his series of images on the biblical ruler Nebuchadnezzar.

Isaac Newton is shown sitting naked and crouched on a rocky outcropping covered with algae, apparently at the bottom of the sea. His attention is focused upon diagrams he draws with a compass upon a scroll. The compass is a smaller version of that held by Urizen in Blake's The Ancient of Days.

Blake's opposition to the Enlightenment was deeply rooted. In his annotation to his own engraving of the classical character Laocoön, Blake wrote "Art is the Tree of Life. Science is the Tree of Death." Newton's theory of optics was especially offensive to Blake, who made a clear distinction between the vision of the "vegetative eye" and spiritual vision. The deistic view of God as a distant creator who played no role in daily affairs was anathema to Blake, who claimed to regularly experience visions of a spiritual nature. He contrasts his "four-fold vision" to the "single vision" of Newton, whose "natural religion" of scientific materialism he characterized as sterile.

Newton was incorporated into Blake's infernal trinity along with the philosophers Francis Bacon and John Locke.

Blake's print would later serve as the basis for Eduardo Paolozzi's 1995 bronze sculpture Newton, after William Blake, which resides in the piazza of the British Library.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Newton (Blake)