It's St. Patrick's Day! And while we all may be Irish today, these artists are Irish all year round.

Ireland may be famous for its literature, its beer, and its patron saint, but did you know that the Emerald Isle has also produced a number of excellent visual artists? Following the rich legacy of the Early Christian period, known for such works as the Book of Kells and the Ardagh Chalice, art in Ireland has continued to thrive after the medieval era. The last few centuries have seen a flowering in Irish art, drawing on the lyricism of the land, Celtic roots, as well as imported traditions, that deserves a place in any art history textbook. So to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day, why not take a look at some of Ireland’s greatest artists and let that one thirty-second part of you that really is Irish swell with pride!

1. Sir Frederic William Burton (1816-1900)

Hellelil and Hildebrand, the Meeting on the Turret Stairs. The National Gallery of Ireland.

Hellelil and Hildebrand, the Meeting on the Turret Stairs. The National Gallery of Ireland.

An accomplished watercolourist and draughtsman, Burton grew up in Co. Clare, was educated in Dublin, and trained as a miniaturist. An expert in archeology and art history, he was appointed director of the National Gallery in London in 1874, where he acquired superstar works by Leonardo and Holbein for their collection. An admirer of the Pre-Raphaelites, he was friends with Millais and Edward Byrne-Jones, and wanted painting to both beautify nature and tell a story. This 1864 painting, voted Ireland’s favorite, demonstrates that Pre-Raphaelite influence, depicting two star-crossed lovers, Hellelil and Hildebrand, in a moment of intimate arm-worship on a winding turret stair. The story comes from a medieval Danish poem about a young woman and her guard who fall in love, only for her father to order her seven brothers to kill him. Plot twist: he kills six of her brothers, only to be killed by the last amidst a swirl of family drama. How did Burton achieve the detail and intensity of hue if he was working primarily with watercolor? The answer can only be lots of layers, a little bit of gouache, and a whole lot of magic.

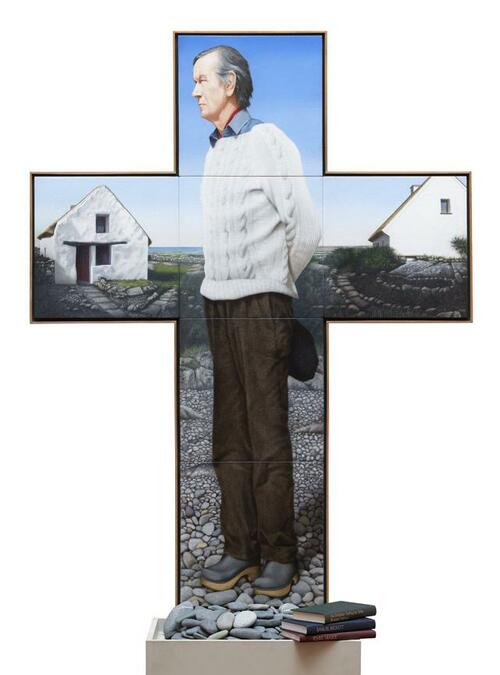

2. Robert Ballagh (b. 1943)

Portrait of Noël Browne (1915-1997), Doctor, Politician and Campaigner. National Gallery of Ireland.

Born to a lower middle-class family of professional sports players in Dublin, “Bobby” Ballagh’s only artistic training comes from a stint as assistant to Michael Farrell. While usually labeled a pop artist or hyper-realist, he also credits his style to the art of his homeland, which, like that of the rest of Northern Europe, has a history of being small and highly detailed. Firmly believing that art should belong to the people, Ballagh uses art for activism, empathy, and democratic discussion. This cruciform, trompe-l'œil portrait, which spills out into the viewer’s space, depicts Noël Browne, an Irish doctor and politician who was instrumental in largely eradicating tuberculosis in Ireland. As Minister of Health, Browne proposed legislation that would allow women and children under 16 access to free healthcare, a proposal that drew ire from the Catholic church and brought about the fall of the inter-party government. Perhaps the cross shape, which Ballagh had not originally intended for the composition, can be read as respect for Browne’s compassion, as well as a sharp jab at the Church. Ballagh has opinions, alright, and he isn’t afraid to share ’em.

3. Sarah Purser (1848-1943)

Le Petit Déjeuner. National Gallery of Ireland.

Le Petit Déjeuner. National Gallery of Ireland.

Born in County Dublin to a well-off family that had roots in the beer trade (you guessed it, Guinness) as well as the intelligentsia, Purser was expected to learn how to be a lady at a fancy school in Switzerland and then sit quietly at home and wait for a husband. Instead she went to Paris, where she studied with the impressionists and became friends with Degas and Berthe Morisot before heading back to Ireland, where she was to have a lasting impact on the art scene. While she was a successful portrait painter, going through British society “like measles” (her words, not mine), her finest works, like Le Petit Déjeuner, depict mundane moments with the exquisite subtlety of the best of the Impressionists. More than a painter, Purser was also a fierce and tireless organizer, founding the Friends of the National Collections of Ireland, establishing the Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane, and forming the stained-glass studio An Túr Gloine (The Tower of Glass), whose work graces the windows of many a church in Ireland today. She herself continued to design stained glass and run the studio until her death at age 94, an inspiration to us all.

4. Harry Clarke (1889-1931)

St. Patrick Preaching to his Disciples. St. Michael’s Church, Ballinasloe.

Perhaps the most gifted stained glass artist of the Irish Arts and Crafts movement, Harry Clarke did not work in the An Túr Gloine circle as his father already ran his own Church decoration company with a stained glass division. While working in his father’s studio Clarke studied at the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin, winning scholarships that enabled him to travel to view Medieval stained glass in France and England. Influenced by his travels as well as the Art Nouveau and Symbolist movements, he developed a unique style characterized by delicate, elongated figures and a mystical, dreamlike atmosphere. His work can be seen in many churches throughout the British Isles, striking just the right note between individual creativity and tradition. This stained glass window, depicting St. Patrick himself, demonstrates Clarke’s finesse as well as the magnificent color Irish stained glass artists were able to achieve. Clarke also made a name for himself as a book illustrator, working on editions of Geothe’s “Faust,” Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, and Edgar Allen Poe’s short stories. The drawings for these are just as polished, imaginative, and enchanting as you could ever desire, though be warned: sometimes they can get pretty spooky.

5. Mainie Jellet (1896-1943)

Decoration. National Gallery of Ireland.

The first cubist painter in Ireland was a woman, Mary Swanzy, whose landscapes were informed by cubist sensibilities. But it was in the hands of another woman, Mainie Jellet, that cubism finally revolutionized the Irish art world. Born in Dublin, Jellet was educated in London under Walter Sickert, as well as in Paris, where she and her Irish bestie Evie Hone sought the tutelage of Albert Gleizes to teach them his cubist ways. Jellet yearned for purity of form and color, and her studies led her to use austere cubist abstraction to explore religious themes. One of the first purely abstract works ever to be exhibited in Ireland, Decoration is based around a central shape, around which other shapes ripple out in a rhythm of line and color. Its pentagonal shape and choice of hues evoke traditional Madonna and Child imagery without devolving into the figurative art with which Ireland was far more comfortable. And indeed, Irish critics were pretty uncomfortable with this work, even daring to call it “sub-human”. (Because apparently abstract art is sub-human, even though humans are the only earthly beings capable of abstract thought. Right.) Nevertheless, Jellet persevered, teaching in Dublin and going on to found the Irish Exhibition of Living Art with Evie Hone and others to challenge the Royal Hibernian Academy. This move was influential, allowing there to be multiple groups of artists in Ireland for the first time and creating vital discourse on the Emerald Isle with the art movements on the continent.

6. Sir John Lavery (1856-1941)

Lady Lavery as Cathleen ni Houlihan. Collection Central Bank of Ireland, Dublin.

Born in Belfast and orphaned at a young age, Lavery studied art in Glasgow and then in France, attracted to the plein-air movement. Although he worked extensively in London, where he was influenced by his friend James McNeill Whistler and even worked as an official artist for the British government during WWI, Lavery never strayed too long from Ireland. He had deep interest in the Irish War for Independence and even lent his London home to be used as the negotiation grounds for the Anglo-Irish peace conference. The fate of Ireland was near and dear to his heart, and this 1928 painting may just be the most Irish painting there is. Commissioned by the Irish Free State to create an image of Cathleen ni Houlihan, the personification of Ireland, for their currency, Lavery painted his second wife, Hazel, as Cathleen, with her arm resting on the national symbol of Ireland, the harp. Though traditionally depicted as old, poor, and in need of young men to fight for the freedom of Ireland, here Cathleen is young and beautiful, perhaps to celebrate the new nation’s own greenness, or perhaps because Lavery couldn’t help it if his wife and favorite muse looked like a 1920’s movie starlet. With both sorrow and hope in her eyes, this quintessentially Celtic image continued to grace Irish currency, albeit in watermark form, until 2002 when the Euro was introduced.

So there you have it. Six amazing Irish artists, and that means six more things about Irish culture to celebrate tonight! So get out there and enjoy yourself!

I’rish you the Happiest of St. Patrick’s Day's, high on kisses and low on pinches!

Sources

- Arnold, Bruce. Irish Art: A Concise History. London: Thames & Hudson, 1977.

- Peter Harbison, Homan Potterton, and Jeanne Sheehy. Irish Art and Architecture from Prehistory to the Present. London: Thames & Hudson, 1978.

- https://www.nationalgallery.ie/hellelil-and-hildebrand-meeting-turret-s…

- https://www.adams.ie/irish-artist-directory/robert-ballagh-art-sold-at-…

- http://www.robertballagh.com/essay.php

- http://onlinecollection.nationalgallery.ie/objects/8745/portrait-of-noe….

- https://artuk.org/discover/artists/purser-sarah-henrietta-18481943.

- https://www.nationalgallery.ie/explore-and-learn/international-womens-d….

- http://www.hughlane.ie/eve-of-st-agnes-by-harry-clarke2

- https://www.nationalgallery.ie/explore-and-learn/international-womens-d….

- https://www.neh.gov/humanities/1999/januaryfebruary/feature/the-irishne…

- https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/homes-and-property/fine-art-a….

Surya Grahan Tips For Pregnant Women