Depression is a nasty condition. Most of the time it leaves you feeling worthless, hopeless, and so fatigued that you have no energy at all. It’s an astounding feat that so many artists have managed to create in spite of their battles with depression. They rise out of the fog just long enough to put something amazing onto the page or canvas. Then, most likely, they crawl back into bed. Here are seven more of those artists across time who made memorable creations despite depression.

1. Gilbert Stuart

Gilbert Stuart’s work has posed problems for a lot of people in the art world because of controversies around whether or not he really created all of it. Sometimes his work would be of outstanding caliber. Other times it looked like an inferior assistant showed up and did a half-assed job just to get it done. The debate about who did what work has raged for a long time. But more recently, another theory has popped up: what if Stuart did create all of this work but it’s so wildly different because of his own changing mental health issues? It’s possible that he had bipolar depression, working wildly different when he was “up” than when he was “down.”

One specific situation speaks to his likelihood of depression. He was commissioned to complete a full-length portrait of John Quincy Adams. He desperately needed the money from that commission. And yet, he refused to finish the job. If he had depression, perhaps he just couldn’t. In depression, you often beat yourself up for your inability to do things “well enough” and so you just become immobilized and don’t do them at all. Then you feel terrible that you didn’t get it done, so you beat yourself up some more. He was known to retire to bed for weeks at a time.

He was also well-known for long periods of winter inactivity. He would start paintings, but then he would set them aside for months at a time. When springtime came around, he’d resume his work. That’s a hallmark of seasonal affective disorder, which is a type of cyclical depression. By midlife, he knew himself well enough to only work when he felt well enough. The thing about depression is that even though it doesn’t necessarily resolve over time, some people are able to understand their own patterns with it well enough to get through them, hanging on until things get better again.

2. Michelangelo

It’s problematic to look back across history and try to diagnose people with mental health issues after the fact. Nevertheless, many are in agreement that Michelangelo likely suffered from recurring depression.

Michelangelo sometimes took longer than objectively necessary to finish his works of art, to the point where at times others had to complete projects for him. Take the Florentine Pieta, for example. He worked on it for eight years, and, in the words of one biographer, “poured his depression over his life into statue.” Depression doesn’t make a piece look so great and Michelangelo finally got so frustrated with the dismal results that he murdered the statue with a chisel. Sculptor Tiberio Calcagni finished that piece.

Michelangelo may be best recognized above all for painting The Sistine Chapel. It’s a monumental achievement, no doubt, but great success doesn’t mean that he escaped great depression. Letters indicate that he dragged through the work in a state of exhaustion and depression. The world is lucky that he managed to complete it at all.

Although Michelangelo was known for his sculpture and painting, he was also a prolific poet. One of his poems, the unfinished canzone, laments the sadness of time lost. Some believe that the poem is a reflection of the depression that he felt during the time that he wasted three years creating the facade of San Lorenzo.

Depression, like all mental health issues, has biopsychosocial roots. In other words, it’s the combination of nature and nurture - our brain chemistry, our genetics, and our environment that lead to depression. We don’t know anything about Michelangelo’s brain chemistry. But we do know that his mother died when he was just 6 years old. And we know that he battled internally with guilt and shame about a homosexual orientation that was considered terribly sinful in his time and place. These things, combined with the stressors surrounding some of his art (such as the unfinished San Lorenzo piece he was commissioned for then not allowed to complete) likely triggered his depression.

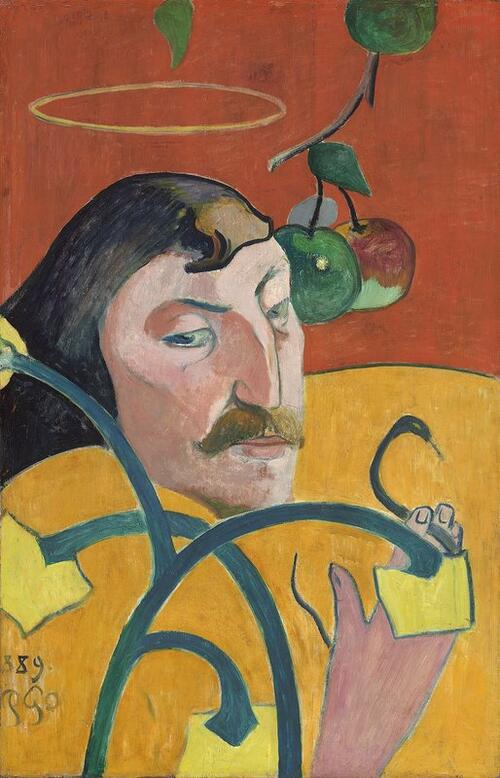

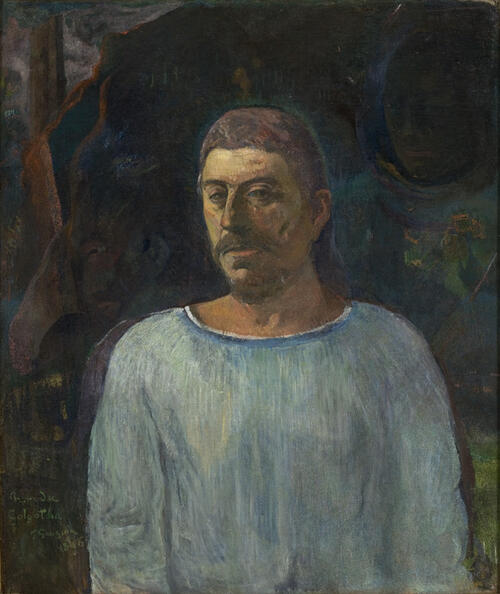

3. Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin had every intention of being a successful suicide. He went off to the mountains alone, drowning himself in arsenic. But he drank just a little bit too much. He made himself so sick that he vomited out all of the poison and became terribly ill but didn’t die. Defeated, he came down off of the mountain, and more or less stopped attempting to create art at all.

Absinthe played an interesting part in Gauguin’s relationship with depression in another way: it linked him to the final moments he spent with Vincent Van Gogh before that other depressed artist cut off his own ear. Gauguin had reportedly gone to spend time with Van Gogh in order to report back to Van Gogh’s brother Theo about his mental state. They got in a huge fight, Van Gogh threw absinthe in Gauguin’s face, and eventually Gauguin just left, shortly after which the ear drama occurred.

Gauguin likely dealt with his own depression for some time before the suicide attempt. After all, the man fled his family for Tahiti where he lived a mostly lonely existence besides the copious amounts of sex he used to keep himself entertained. A few years before the suicide attempt, around the time that he painted Self-Portrait Near Golgotha, he wrote a letter sharing that a number of trials and tribulations (including financial troubles that left him without access to food or medication) were making him feel suicidal. There are hallmarks of depression all over the self-portrait - from the posture to the coloring, it reeks of fatigue. In another letter he wrote that he felt discouraged “to the point that I no longer dare paint and I drag my old body along the shores.”

4. Joan Miró

It’s no secret that Miró suffered from depression. Not only did he share about it widely through his own letters and interviews, but subsequently biographers and critics have done detailed analysis of the role that his depression played in his artistic output. He had chronic recurring depression, the earliest known period of which happened at the age of 18. He basically stayed in bed for an entire season of that year. Although that was the first period of noted depression, he shared that he felt lonely and isolated throughout much of his childhood, with a temperament that naturally leaned towards depression. He frequently described himself as a pessimist, as though depression were a natural state of being for him.

There is a reason that art therapy exists; art can heal us. Reports suggest that perhaps it played this role for the artist. He said in a 1947 interview that when he doesn’t paint he gets “black ideas” that lead to worry, fretting, and gloominess, suggesting that when he does paint the depression eases a bit. He reportedly used meditation, introspection, and spiritual belief to make the darkness work for him, channeling it all into his art. His self-portraits in particular, show not only his mood changes, but also a deep desire to transcend his own depression.

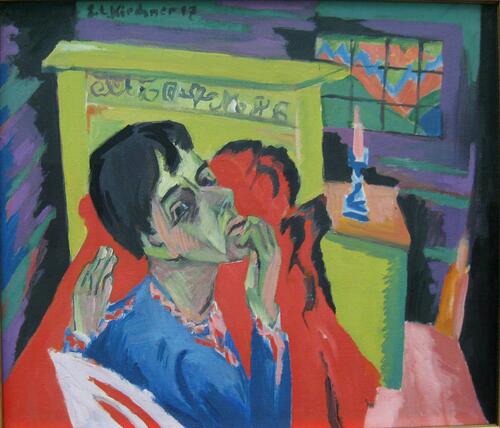

5. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Perhaps the best succinct description of Kirchner comes from the title of a "New York Times" art review: “A Tormented Expressionist, Overlooked in a Brutal Time.” His depression is inextricably linked with world history. He joined the German Army during WWI but quickly couldn’t hack it, had a mental breakdown, and was discharged. That marked the beginning of a long substance addiction with alcohol and morphine, which would become entangled with depression for the rest of his life. He had his first, but not last, stay in a sanatorium after his Army discharge.

Fast forward to WWII. He had spent his life trying to revive German art but Nazi Germany labeled him a degenerate and destroyed more than 600 pieces of his artwork. Kirchner was living in Switzerland, saw the Nazis encroaching on the territory and was certain that they were coming to destroy him just as they had his art. He wanted to die by his own hand before that could happen. He reportedly tried to convince his girlfriend Erna to join him but she didn’t want to die. He went outside and shot himself through the heart.

Notably suicide and depression aren’t always linked; although one commonly goes hand in hand with the other, it’s possible to commit suicide without being depressed. So we can’t say for sure that depression motivated the suicide. But Kirchner’s long history of depressive periods is well documented. His own self-portraits offer the greatest depiction. In particular, Selbstbildnis als Soldat (Self Portrait as a Soldier) and Selbstbildnis als Kranker (Self Portrait as a Sick Man) (shown above), both of which were completed around the time of his first sanatorium stay, show a markedly depressed human being. Interestingly, one of his final paintings, Flock of Sheep, completed just before he died, looks considerably calm and peaceful. This can happen when someone has decided that they are ready to die by suicide; having accepted the fate, they feel less tortured. This doesn’t diminish the torturous nature of depression but reveals that having found a way out from it offers some relief.

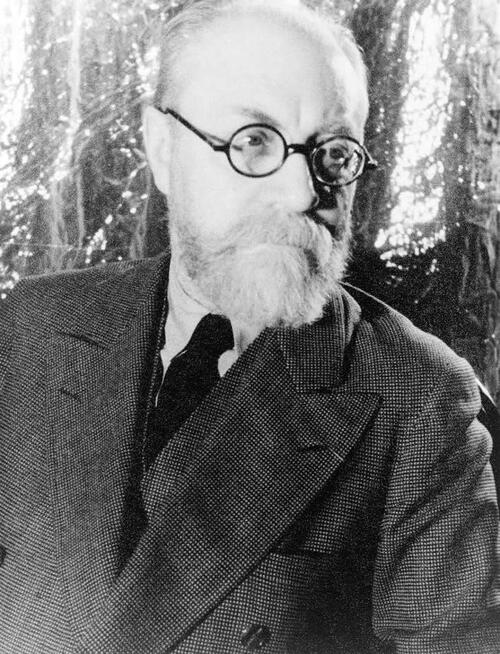

6. Henri Matisse

Depression isn’t easy to cure but sometimes you can find ways to circumvent the symptoms. Matisse found dance, singing, and if all else failed, whistling could help him deal with his most depressive periods. And he was certainly inclined to depression, but he also tried desperately both to understand it and to escape it. At one point he created a “scale of suffering” to determine of all his worries what bothered him least (lack of money) and what bothered him most (losing his love for his work).

But he couldn’t always reach understanding. Sometimes his moods would get black. Then he would try to dance, and if he couldn’t dance, he would try to sing, but sometimes even the simplest melody would elude a depressed mind so then he would whistle. And it wouldn’t fix the problem but he’d get a little bit of a lift in his depressed move, enough that he could move forward, in spite of the depression.

Matisse wasn’t the only one in the family to struggle with depression. In 1911, he spent time apart from his wife Amelie, and their letters suggest that both of them struggled with depression during this time. He suffered from alternating feelings of panic, insomnia, and exhaustion and said that the only thing that ever made him feel better was Amelie. In turn, her letters reflect feelings of aimlessness, boredom, irritability, and gloom. Matisse would write her back with practical lists of simple tasks to take care of, which may sound cold but when you’re dealing with depression, sometimes a practical “get at least one thing done today” approach is all that can muster you out of bed. Given his own knowledge of depression’s workings, he may have just been trying to help.

Interestingly, Matisse seems to have been drawn to women struggling with depression. One summer he and his wife were doing well when their happy time was marred by the fact that Henri invited his model/student Olga Meerson along, causing jealousy and arguments and generally stirring up drama. It didn’t help that Meerson, too, had a history of “black thoughts” that caused insomnia, worry, and depression. It’s unclear of Amelie was also depressed during this time but if not then she was probably just holding it back as much as possible. She was known for holding in all emotion to the point where finally she just completely broke down, both mentally and physically.

7. Albrecht Dürer

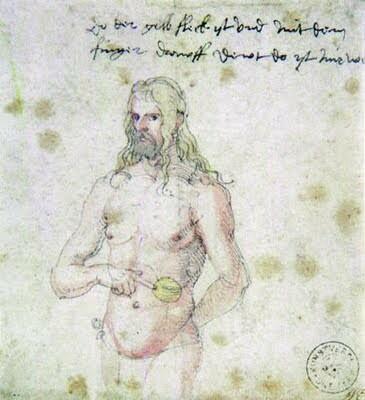

Before we called it depression, we called it melancholia (which is arguably only one form of depression as we understand it today). Albrecht Dürer has an engraving of the same name, and some say that it’s a self-portrait of his own depression. The medical understanding of depression was, obviously, different during his time. People still followed medical ideas based on The Four Humors, a Greek idea from Hippocratic medicine relating different symptoms (such as phlegm) with different illnesses and temperaments. We don’t have to get into all of the ancient medicine here but the argument goes that the spleen was ultimately linked with melancholy and that Durer both drew and mentioned his spleen several times throughout his life, perhaps in an effort to try to get doctors to pay attention to his depression.

In particular, he has a 1913 drawing called The Sick Durer, a self-portrait pointing to his yellowed spleen. This follows on the heels of a decade of stressors, including watching his father die. In 1913 and 1914, his godfather and mother both died as well. Grief can turn into depression when not properly processed. That brings us to the Melencolia I etching. The name itself clues us in to the topic. Dark features, slouched posture, and the inclusion of symbols that represent depression all help drive the point home. And this takes us back to the Greeks because Melancholia itself was one of the four humors - associated with cold, dry qualities, black bile, and depression - but also with creativity and art.

This post is part of our continuing series on Mental Health Art History: Artists Creating Despite A Diagnosis. In addition to our posts on other artists with depression (also see Part 2), we’ve covered bipolar artists and artists with schizophrenia.

Cover image by Emma Darvick

Sources

- Aronson, J. and Ramachandran, M. “The Diagnosis of Art: Ernst Ludwig Kircher’s ‘Nervous Breakdown’.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2019 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3072252/

- Berndt, Ginny. “Albrecht Durer’s Melancholia I: A Self-Portrait.” 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2019 from https://www.lagrange.edu/resources/pdf/citations/2010/02Berndt_Art.pdf

- Bogousslavsky, J. and Tatu, L. “Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists.” Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. 2018.

- Dorra, Henri. “The Symbolism of Paul Gauguin: Erotica, Exotica, and the Great Dilemmas of Humanity.” University of California Press. 2007.

- Evans, Dorinda. Gilbert Stuart and the Impact of Manic Depression. Routledge. 2013

- Gayford, Martin. “Michelangelo: His Epic Life.” Penguin UK. 2013.

- Gunderson, John G. “Borderline Personality Disorder: A Clinical Guide.” American Psychiatric Pub. 2009.

- Ludwig, Arnold M. “The Price of Greatness: Resolving the Creativity and Madness Controversy.” Guilford Press. 1995.

- Matisse, Henri. “Chatting with Matisse: The Lost 1941 Interview.” Getty Publications, 2013.

- Maurer, Naomi. “The Pursuit of Spiritual Wisdom: The Thought and Art of Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin.” Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. 1998.

- Michelangelo. “The Complete Poems of Michelangelo.” University of Chicago Press. 2000.

- Schildkraut, Joseph. “Miro Offers Case in Point of Creativity’s Link to Depression.” The New York Times. Oct 24, 1993. Retrieved July 20, 2019 from https://www.nytimes.com/1993/10/24/opinion/l-miro-offers-case-in-point-…

- Smith, Roberta. “A Tormented Expressionist, Overlooked in a Brutal Time.” The New York Times. March 7, 2003. Retrieved July 20, 2019 from https://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/07/arts/art-review-a-tormented-expressi….

- Somervill, Barbara A. “Michelangelo: Sculptor and Painter.” Capstone. 2008.

- Spurling, Hilary. “Matisse the Master: A Life of Henri Matisse, the Conquest of Colour, 1909-1954.” Knopf, 2005.

- Storr, Anthony. “Solitude: A Return to the Self. “ Simon and Schuster. 2005.

- “The Tragedy of Avant Garde Artist Ernst Kirchner.” CBS News. January 24, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2019 from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-tragedy-of-avant-garde-artist-ernst-ki…

- Wolf, Norbert. “Ernst Ludwig Kirchner 1880-1938: On the Edge of the Abyss of Time.” Taschen. 2003.

Comments (3)

A stunning summary of artists impacted by their mental health.

what an interesting article to read. Kathryn did a huge job for us