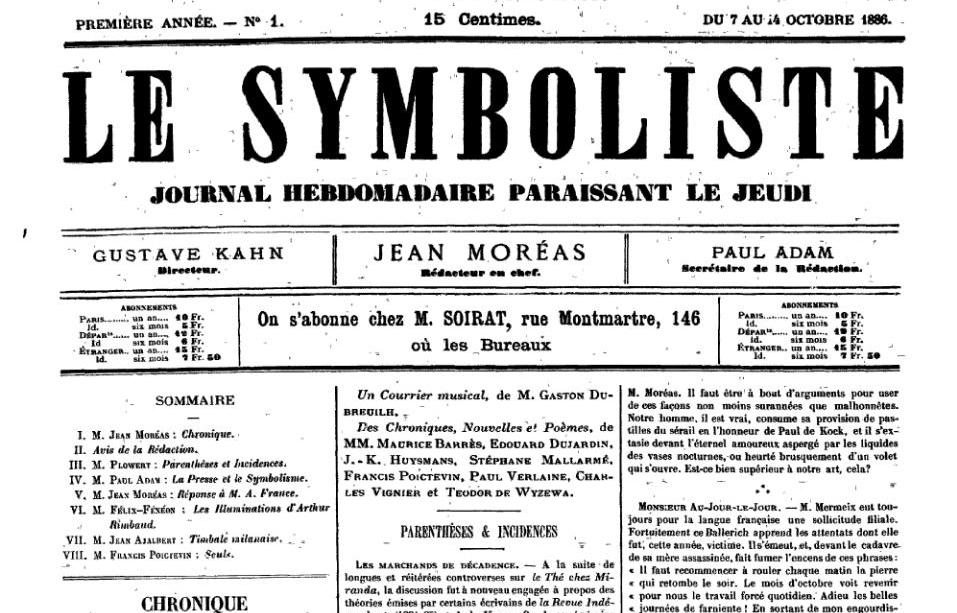

The Symbolist Movement was born in 1886 as a literary movement by Jean Moreas, in a manifesto published in Le Figaro. A reaction to the rampant materialism and rationalism that dominated Western culture, Moreas stressed pure subjectivity and the expression of an idea over all else. 1891 gave Symbolism as an art movement its definition, thanks to art critic Albert Aurier. He described it as art that reflected an emotion or an idea in a simplified, non-naturalistic style. Sounds like the beginnings of abstract art, doesn’t it?

Even though Aurier proclaimed Paul Gauguin the foremost Symbolist artist of his generation, works done in the Symbolist style were actually made a decade earlier by artists such as Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. The trio’s work would exemplify the early stages of the Symbolist movement. While still very much grounded in realism, the early Symbolists made extensive use of biblical and Greco-Roman mythology, monsters, and themes throughout. Love, fear, anguish, and death were major themes in their works. They also really liked using women, particularly ones that adhered to virgin and femme fatale archetypes. Of the three, de Chavannes would have the biggest influence on the next generation of Symbolists with his broad strokes and shapes in the styles of Paul Gauguin and a younger Pablo Picasso, who at this time had a more figurative style.

Study for Patriotism by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, 1893, in the Ohara Museum of Art

By the 1880s, the Symbolist style would really kick into overdrive. The Symbolists painters of this decade progressed into a more abstract style, using broad strokes of color and flat forms in their aim to escape the decadence of the civilized, industrial world. Unlike the earlier artists, the Symbolists of this decade developed their style independent of each other. There’s quite a few Symbolist artists from this time, but I want to focus on three: Paul Gauguin, Edvard Munch, and Gustav Klimt.

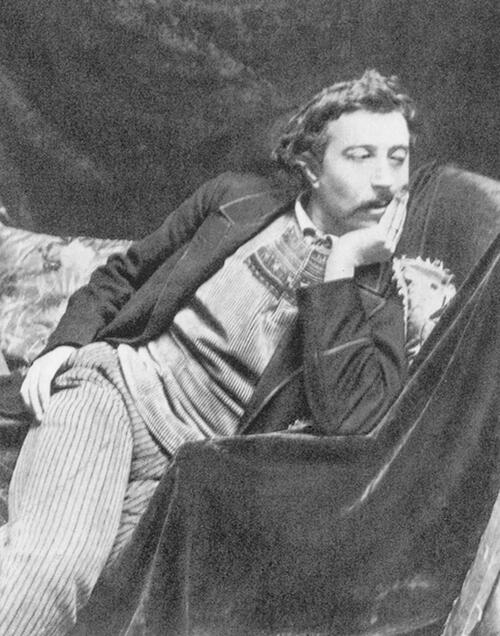

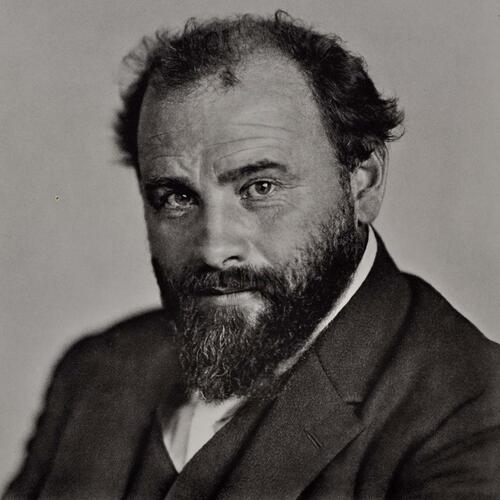

Paul Gauguin, a former post-Impressionist, instead of looking back to antiquity, looked to rural and indigenous cultures for inspiration. He started first in Brittany with the Breton peoples before moving to the South Seas to the island of Tahiti in a quest to find a lost paradise untouched by the Western world. Perfect excuse to end up married to a Tai woman, Pau’ura, and sire two children with her. His descendants still inhabit the island.

Te aa no areois (The Seed of the Areoi) by Paul Gauguin, 1892, in the Museum of Modern Art in New York

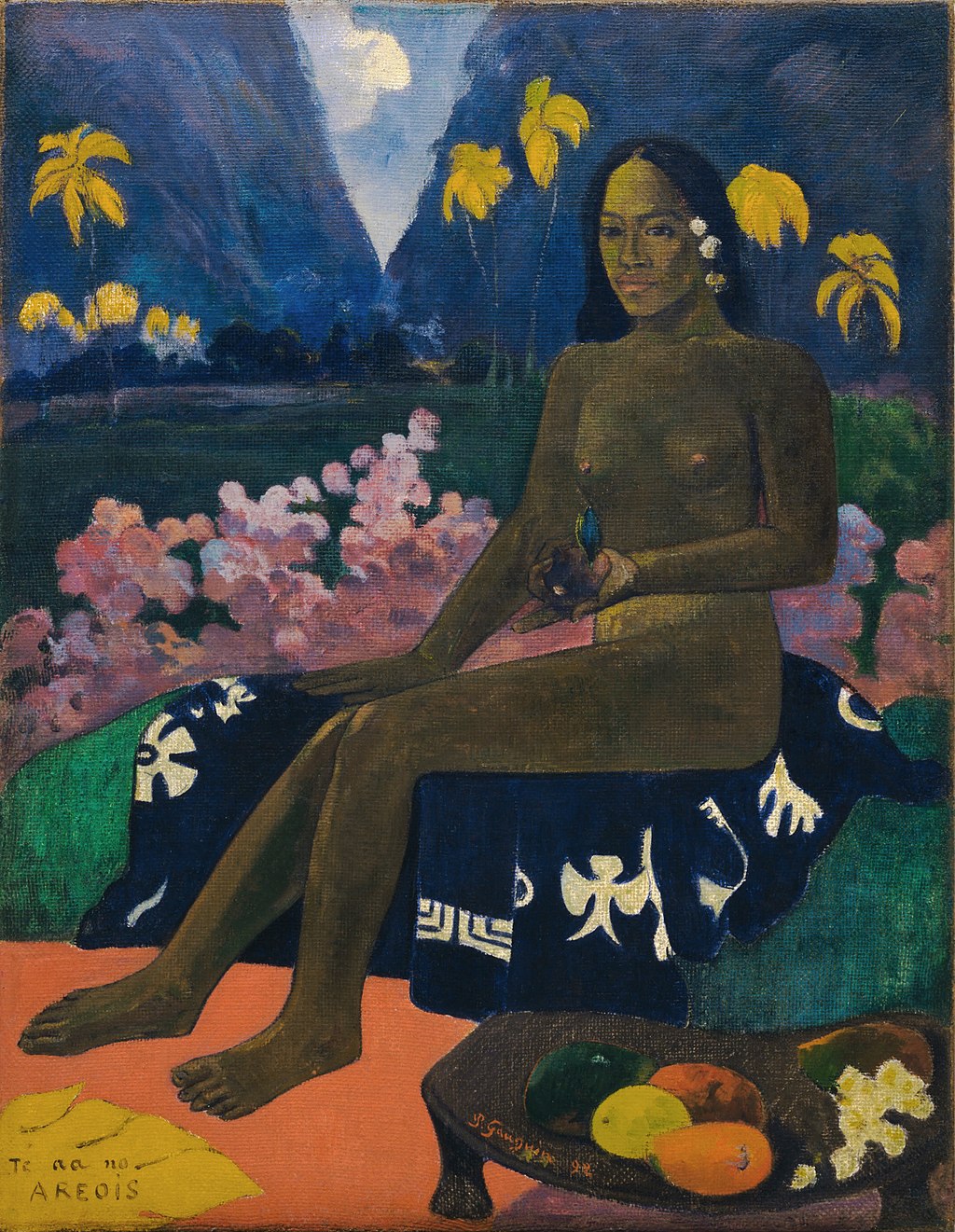

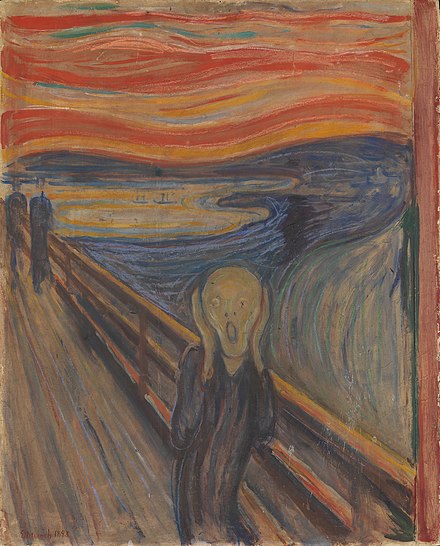

Edvard Munch, on the other hand, was much more macabre. The Norwegian was in cahoots with the French salons that propagated the Symbolist movement before settling in Germany in the 1890s. Unlike Gauguin and the early Symbolists, his work focused the real anxieties of modern existence: illness, despair, and mental suffering. He himself had suffered immense tragedy, losing both his mother and sister to tuberculosis. His most famous work, The Scream, is the shining example of a visual representation of what it means to be internally screaming.

The Scream by Edvard Munch, 1893

Gustav Klimt paired his realistic figures with highly textured, golden, ornamental patterns, basically the analog version of going onto Photoshop, using the lasso tool, and replacing the insides with patterns. He had a fascination with the female figure, covering both the creative and destructive aspects of female sexuality.

Adele Bloch-Bauer's Portrait, 1907, in the Neue Galerie in New York

The Symbolist movement had ties and parallels to other movements throughout its duration, walking hand in hand with post-Impressionism, Neoclassicism, Romanticism, and Art Nouveau. As it grew into a more abstract style, Symbolism would lay the groundwork for the abstract movements, such as Expressionism and Cubism, that would dominate the rest of the 20th century.

Sources

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. 2013. “Symbolism.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. May 22, 2013. https://www.britannica.com/art/Symbolism-literary-and-artistic-movement.

- Danielsson, Bengt, and Reginald Spink. 1966. Gauguin in the South Seas. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- “Edvard Munch and His Paintings.” n.d. Edvard Munch - Paintings, Biography, and Quotes. edvardmunch.org. Accessed December 27, 2018. https://www.edvardmunch.org/.

- Myers, Nicole. 2007. “Symbolism.” The Met's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. August 2007. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/symb/hd_symb.htm.

Check out Latest Surya Grahan Tips For Pregnant Women