Paolozzi as the god of art, fire, and other dangerous things? Photo by Ezinda Franklin-Houtzager

This massive 23 ft statue of Vulcan guards the patrons of the cafe at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. His gigantic head rears up through the atrium to the very top of the building. Who knows what Edoardo Paolozzi had in mind when he welded this steel giant together. Could it be the largest self-portrait ever?

What we know is that Vulcan is the god of art, in the form of alchemy, fire, the foundry, the smith. And Paolozzi’s work with scrap metal and everyday objects was an alchemy that blended the best in humanity and a futuristic metal-based vision.

Vulcan also brings to mind Paolozzi’s physicality. English newspapers missed no opportunity to comment on his broad, swarthy looks. The Telegraph, in its obituary no less, described him as ‘baboon-like in appearance.’ The more liberal Guardian, not to be outdone, reported that his wife’s ‘handsome English looks made a striking contrast with his thick-set Mediterranean appearance.’

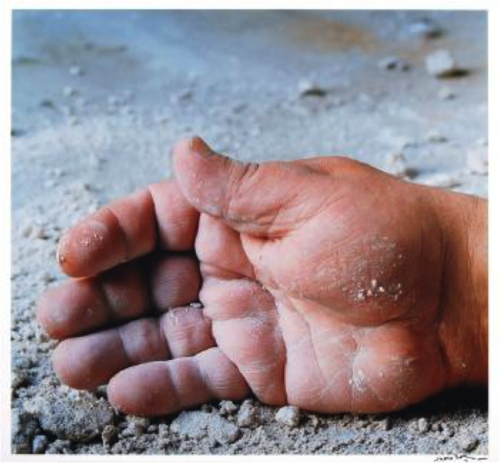

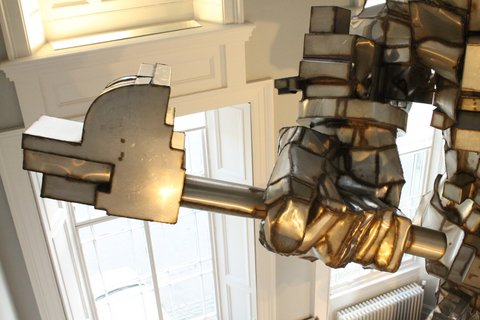

No matter your ethnic-take on his body, this man was physically powerful. Take a look at his hand. There’s no denying that it is the same fist, rendered in steel, that is wrapped round Vulcan’s hammer.

Paolozzi’s well-worn sculpting right hand.

Vulcan’s right hand wielding the black smith’s hammer. Photo by Ezinda Franklin-Houtzager

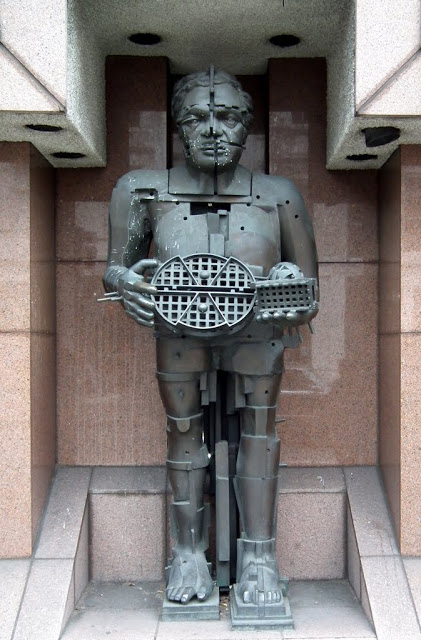

Then there is his sculpture of the Hephaestus. A London-Paris property group commissioned a piece twelve years before Vulcan that was to incorporate a self-portrait of the artist. What Paolozzi created wasn’t the Vulcan but Hephaestus, his Greek incarnation and who made Achilles’ armor, Eros’ bow and arrows, and Hermes’ winged helmet and sandals. The sculpture is based on a bust of him that pointedly included a broad chest, with chest hairs and all. The artist probably identified with Hephaestus because the god of artisans and blacksmith built automatons to work for him. The return to this god near the end of his life, in the form of a welded steel Vulcan, must have meant something special to him.

The artist as Hephaestus. 1987.

Why would we even want Vulcan to be autobiographical? Well, if you have time and can swing it, take a walk to the upper balcony of the museum and look Vulcan in the face. You’ll see. That’s the point where this incredible beast becomes incredibly human. There is emotion in the welded angles of his face. Simply put, you want to feel that you’ve met him, that you’ve known him.

That face! Photo by Ezinda Franklin-Houtzager

Paolozzi was an early Sartler and gave his entire collection and studio to the Scottish people. He wanted his work to be accessible and present in the everyday lives of people. ‘If it [sculpture] is out in a railway siding or it’s stuck under your nose,’ he observed, ‘for the ordinary commuter who might not otherwise go to a sculpture park, they can’t miss it.’

Honoring this solidarity with his fellow humans, the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art put Vulcan where it cannot be overlooked, if ever it could, in the middle of its atrium. As it’s part of the coffee shop you can look up between bites of a lemon slice and enjoy the great geometric feet and angular organic assemblage.

Vulcan in coffee shop. Photo by Ezinda Franklin-Houtzager

We’ll never know if Paolozzi made the god in his own image but shortly after completing the piece reality and myth seemed to merge. Vulcan is often portrayed as lame, with a useless leg, broken when he was a baby as he was cast out from among the gods. Less than two years after he completed Vulcan fate struck the artist himself and with a stroke confined him to a wheelchair for the few remaining years of life.

By Mrs. Rivaat Zarlif

Sources

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1488447/Sir-Eduardo-Paolozzi…

- Sir Eduardo Paolozzi

- http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/apr/22/art

- Imogen Tilden, Sculptor and pop art founder Eduardo Paolozzi dies