More about Red Stripe Kitchen

- All

- Info

- Shop

Sr. Contributor

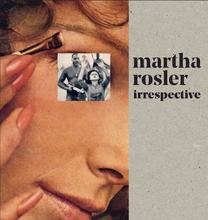

For Martha Rosler, there’s something very troubling brewing just beneath the surface of the picture-perfect home.

Lasting about twenty years, the Vietnam War occupied the minds of people around the world, and some artists were exceptionally vocal about their stance on the conflict. Perhaps the most well-known example is Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s two-week “bed-in,” in which staying in bed somehow counted as a protest. Unlike those two ultra hippies who probably just wanted an excuse to not leave their blanket burritos, Rosler was more active in her approach to artistic activism.

Imagine turning on the TV at night only to see the latest, horrifying footage of the Vietnam War right in your living room. Well, when you only had like eight channels to choose from, I guess that was what everyone watched. At the time, the Vietnam War was the most documented armed conflict yet. No other war had been televised to the extent that the war in Vietnam was. And as Martha Rosler points out, this had a pretty weird effect on the American psyche. With 1969 marking the height of the United States’ involvement, Rosler was already two years into the series Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful, a body of photomontages that deconstructed the American media’s normalization of images of war violence.

In addition to political commentary, the series also asserts a 1970s feminist agenda – but just a little less focused on vaginas than her contemporaries. Rosler didn’t feel the need to pull a long scroll of poetry out from inside her vagina. Nor did she care much for sticking bubble gum vulvas onto her own body, à la Hannah Wilke. No, Rosler was a bit more subtle than that. But this doesn’t mean that her work is any less powerful or thought-provoking than the other vagina-obsessed artists. To stake her claim in this intense wave of feminism, Rosler sourced her images from lifestyle magazines that predominantly targeted women. In doing so, she showed the American cultural association of women with the domestic sphere and the notions of femininity embedded within homemaking.

Rosler urged 1970s-era Americans to rethink their relationship to consumer culture – what’s the real cost of that dream kitchen? And what’s with the obsession with having an impressive home when so many people from both sides of the conflict are dying overseas? To reach a wide audience and instigate these questions as much as possible, she photographed her photomontages and encouraged people to use them for antiwar rally fliers and alternative news publications. A certain orange someone definitely would’ve called “fake news” on Rosler’s strong calls for American accountability.

Fifty years later, these images are still just as jarring. After all, the United States has continued its involvement in controversial conflicts. Thankfully for us art-minded folks, Rosler has continued her critique of the nation’s foreign policies. In 2004, she updated the Bringing the War Home idea by producing more photomontages focused on the war in Iraq.

Sources

- Bee, Harriet Schoenholz, Cassandra Heliczer, and Sarah McFadden. MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from The Museum of Modern Art, New York. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1999.

- Fineberg, Jonathan. Art Since 1940: Strategies of Being. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc., 2011.

- Riding, Alan. “Arts Abroad; The Vietnam War, as Seen in Art From the Other Side.” The New York Times. October 22, 2002. http://www.nytimes.com/2002/10/22/arts/arts-abroad-the-vietnam-war-as-s…. Accessed July 13, 2

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Martha Rosler. Collection Online. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/martha-rosler. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Red Stripe Kitchen. Martha Rosler. Collection Online. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/13810. Accessed July 13, 2017.