More about One Hundred Horses

Sr. Contributor

Giuseppe Castiglione, also known by his Chinese name Lang Shining, transcended national boundaries with pretty pictures of horsies.

We all knew that one kid in elementary school who constantly drew pictures of horses: leaping over rainbows, napping in stables, and adorned with lustrous manes. They are beautiful creatures that have also figured significantly in art history. Rosa Bonheur loved them, and Maurizio Cattelan uses them as a signature, morbid style. Horses, as well as other animals and elements of nature, have an even longer tradition in Chinese art, symbolizing royal strength and the power of the emperor.

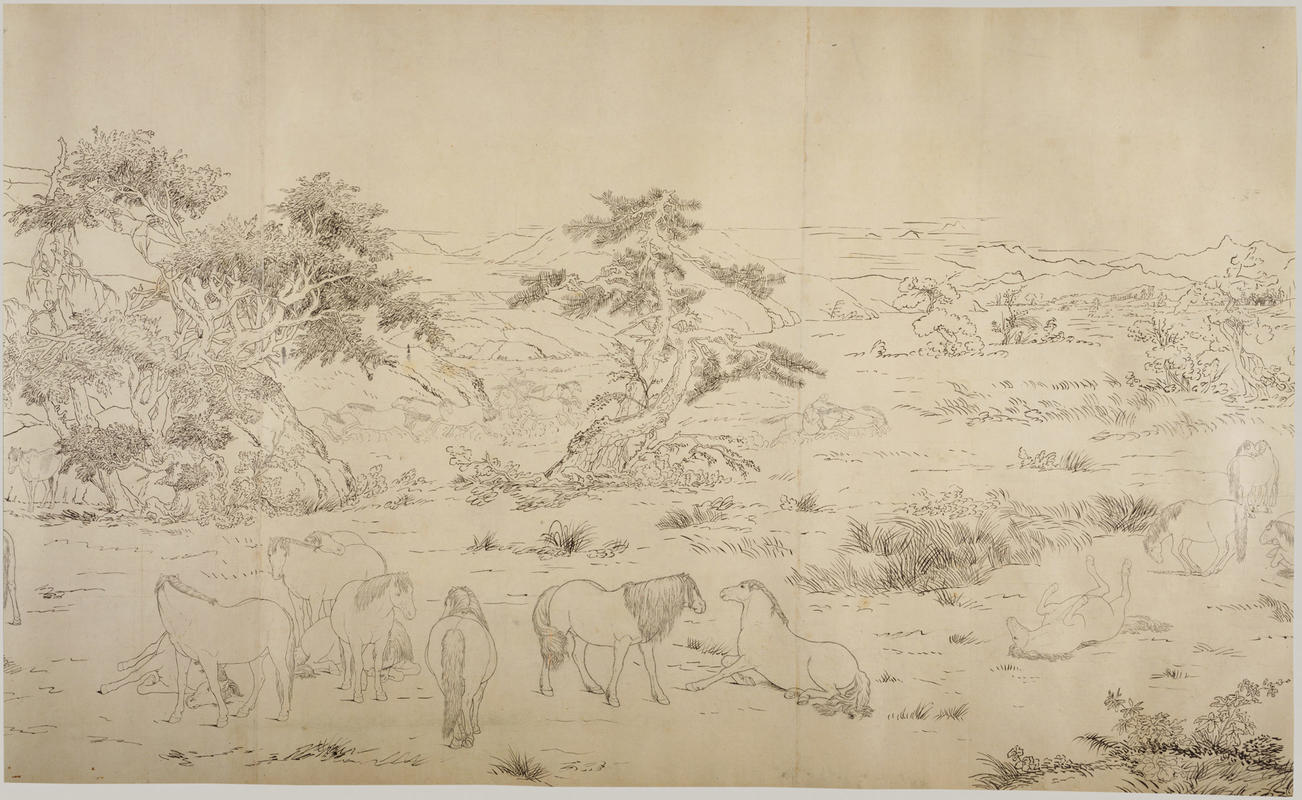

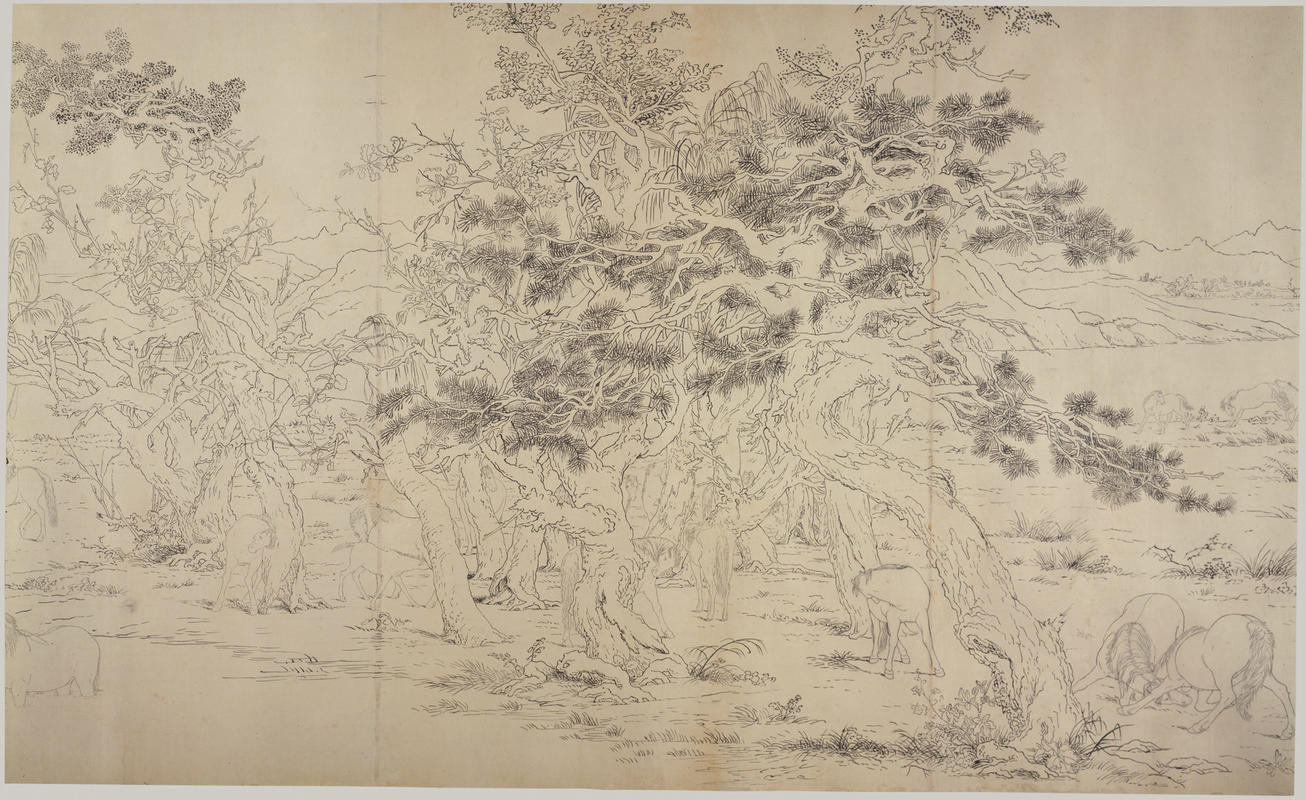

It’s no surprise, then, that this eighteenth-century scroll features more horses than an episode of BoJack Horseman. Castiglione created this monumental work of one hundred horses in their prime for the Qianlong Emperor, who believed that these animals reflected his own glory as a powerful, Chinese emperor. Despite the grandeur of this work – it clocks in at thirty-seven inches tall and over twenty-five feet long – this isn’t even its final form. It’s a preparatory drawing for an even more beautiful silk painting, currently in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan.

Castiglione was an Italian transplant living and working in China, originally there as a Jesuit missionary until he got noticed for his artistic talents. Before coming to China, he trained in Western realism and painted murals in Italy. His unique blend of European techniques and styles with Chinese themes and motifs inspired a new aesthetic movement in Chinese royal court art. The jagged mountains, lush valleys, and trees that dominate this drawing reflect the long tradition of Chinese landscape painting. However, Castiglione’s Western training in one-point and atmospheric perspective allowed him to create a more realistic image of the land than the flat style more common in Chinese art. Castiglione’s mastery of these perspectives certainly would have made his forebears from the Italian Renaissance proud.

Castiglione lived in the Manchu court for more than a decade and had served three different emperors by the time he made this drawing. As a foreigner, he had to prove himself before taking on this scroll, which was no small feat. From beginning this preparatory drawing to producing the finished silk painting, Castiglione spent five years working on this masterpiece. Having paid special attention to the horses’ many different colors and attributes, Castiglione’s final version boasts of Western realism and naturalism. Castiglione knew how much the Qianlong emperor loved his tribute horses – fine prize horses that the emperor received from nations that were under his control. The Italian artist quickly became a favorite of the emperor because of his special knack for depicting horses as beautiful and unique creatures that also symbolized the emperor’s own strength and power.

In a difference of cultural opinions concerning the nude body in art, the Chinese emperor slightly censored the final painting. After Castiglione brought the preparatory drawing to the emperor for his approval, Castiglione had to make some changes. The horses and landscape were both up to par for the emperor, but some of the attendants, who were nude from the waist up, were a no go. In the final painting, Castiglione fully clothed these figures to placate his royal patron.

Sources

- Arnold, Lauren. “Of the Mind and the Eye: Jesuit Artists in the Forbidden City in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries.” Pacific Rim Report. The Ricci Institute at the USF Center for the Pacific Rim. 27: April 2003. http://www.ricci.usfca.edu/assets/p

- China Online Museum. “Lang Shining: One Hundred Horses.” https://www.comuseum.com/painting/masters/lang-shining/one-hundred-hors…. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- Department of Asian Art. “Nature in Chinese Culture.” The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2004. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cnat/hd_cnat.htm. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- Glueck, Grace. “Art Review; The Chinese Horse, A Symbol of Power.” The New York Times. October 24, 1997. https://www.nytimes.com/1997/10/24/arts/art-review-the-chinese-horse-a-…. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- National Palace Museum. “Painting Anime: One Hundred Horses.” National Palace Museum. https://theme.npm.edu.tw/exh108/npm_anime/OneHundredHorses/en/index.html Accessed July 22, 2019.

- Shine. “One Hundred Horses.” Shanghai Daily. Now and Then. May 15, 2016. https://archive.shine.cn/sunday/now-and-then/One-Hundred-Horses/shdaily…. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “One Hundred Horses.” https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/44632. Accessed July 15, 2019.