More about Lucretia

- All

- Info

- Shop

Editor

Veronese titled this work Lucretia, but he also could have called it “The Me Too Movement can’t come soon enough.”

Lucretia was a popular subject for Renaissance and Baroque artists. The story itself was first recorded by the Ancient Roman historian Livy in his “History of Rome,” a work largely composed of morality tales, both good and bad, that provided a lot of fodder for the imagination of Renaissance artists. Lucretia was the beautiful and chaste wife of the Roman general Collatinus. One evening Collatinus, while out having a drink with his fellow soldiers, gets to boasting about his wife’s faithfulness. The soldiers decide to surprise each of their wives at home and see which one really is the most chaste. What a fun game! And of course, Lucretia wins. She’s working diligently at her spinning wheel, which is emblematic in Western art of domestic virtue.

But seeing such a chaste lady turns out to be a major turn-on for Sextus, son of the tyrant king of Rome, the Etruscan Tarquin the Proud, and one evening, when Collatinus is in the field, he invades Lucretia’s chamber and threatens to either rape her or kill her and a male servant and leave their naked bodies to be discovered as evidence of adultery. Truly stuck between a rock and a hard place, Lucretia yields to Sextus, and later confesses all to her husband and father. Her husband forgives her, but with her virtue gone, her honor can only be repaired by the taking of her own life, a noble act in Ancient Rome. Her needless and terrible death enrages the Roman populace, spurring a rebellion that ultimately forces Tarquin the Proud and his family into exile in c.509 BC, paving the way for the formation of the Roman Republic. So Lucretia’s death was sad, but also happy because they got a nice new Roman Republic out of the deal.

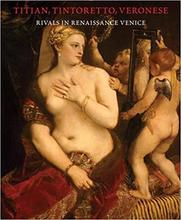

When Botticelli undertook the subject of The Tragedy of Lucretia, he focused on the rebellion that rose up over her dead body (literally, in his case). While Titian and Tintoretto, Veronese’s two rivals in Venice, both painted scenes of the assault and the suicide, it is their images of the former that are the most memorable: large-scale paintings of the nude Lucretia in luxurious surroundings fighting off her dagger-wielding attacker. These conform to standard Lucretia iconography but are notable for the intensity of the action, the stark contrast of beauty and horror, and the question of the viewer’s complicity in the act being witnessed. Instead of painting an erotic Lucretia like his rivals, however, Veronese zeroes in on her sorrowful isolation at the moment of her suicide. While more intimate than his earlier, pageant-like paintings, Lucretia still possesses the luxuriousness and refinement that characterizes his best work, here lending the sorrowful figure such elegance that the violence of her death is considerably mitigated.

Since it was painted in ca. 1585, the painting has been attributed to numerous artists and even just Veronese’s workshop, largely because it differs so much from his earlier works. It was painted in the last decade of Veronese’s life, a mysterious time in terms of his output. His sensual eroticism and bright colors are gone. What still makes it a Veronese is the opulence and the deft handling of light, shimmering off of the deep green fabrics, and glinting off of the finely executed pearls and bracelets. But why his style changed and why he painted a clothed, suicidal Lucretia modestly pulling her garments up around her is not entirely certain.

It may have to do with cultural changes following the Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563, that formed the church’s response to the Protestant Reformation. While the didactic value of art was championed by the Council, they felt the need to lay down rules for picture-making. The big buzzwords were Truthfulness, Clarity, Decorum and Emotional Accessibility (oh, and No Nudity), and violations could lead to heresy accusations, which are never fun. In 1573, Veronese had been called before an Inquisition tribunal because his painting of the Last Supper intended for the refectory of SS. Giovanni e Paolo in Venice contained “indecorous” details, such as as an apostle picking his teeth with a toothpick. Disgraceful, I say. Veronese got off easy, all said and done, but after that incident he may have been less keen to deal with the culture police.

Perhaps that’s why his Lucretia is an Exemplum Virtutis, a type of painting the Council of Trent specifically advocated for because it provided a good moral example to viewers. Even the images of classical deities Veronese painted during this time were transformed into morality tales; his Venus of ca. 1585 is no steamy, reclining nude, but rather is seen gazing at herself in a mirror in a classic gesture of vanity, a serious sin indeed. Lucretia herself was an example of wifely fidelity that made her a great role model in a time when a woman’s sole reason to exist was to produce male heirs for her husband.

Sources

- Alpers, Svetlana. Vexations in Art: Velázquez and Others. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

- De Vecchi, Pierluigi, Giandomenico Romanelli and Claudio Strinati. Veronese: Gods, Heroes and Allegories. Milan: Skira, 2004.

- Hall, James. Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art. 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2008.

- Ilchman, Frederick. Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese: Rivals in Renaissance France. Boston: MFA Publications, 2009.

- “Lucretia, 1664.” National Gallery of Art. Accessed June 20, 2018. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.83.html

- Neuman, Robert. Baroque and Rococo Art and Architecture. New York: Pearson, 2013.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Lucretia (Veronese)

Lucretia is an oil-on-canvas painting by Paolo Veronese from c.1580-1583. This Venetian painting depicts Lucretia in the act of piercing her chest with a dagger after having been raped by the king’s son of Sextus Tarquinius. It is held in the collection of Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

A subject of many works of other artists, such as Titian, Rembrandt and Raffaello Sanzio, in Veronese's painting what is striking is the attention to detail, from the drapery that cloaks the figure to her jewels.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Lucretia (Veronese)