More about John Updike

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

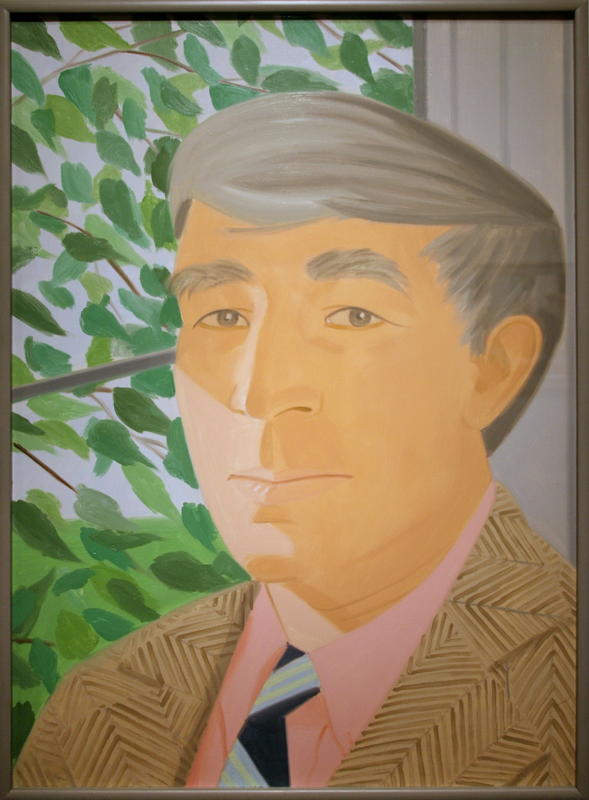

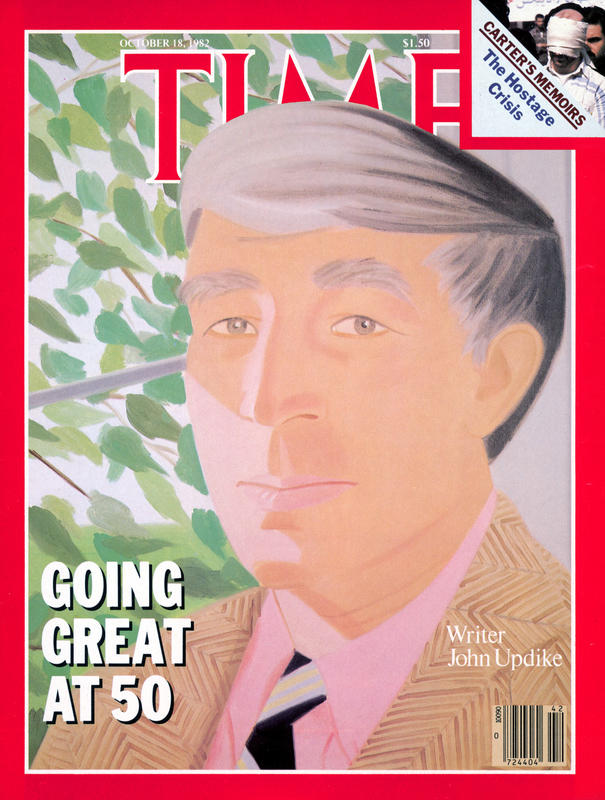

Alex Katz’s serene portrait of John Updike reinforced his place within a small cohort of living writers invited to grace the space between Time's coveted red border.

But it may not have been flattering enough for the prolific writer who prided himself on finishing one novel per year. Or, at least he tried to. Known for heavy-hitters like "The Witches of Eastwick" (anyone who hasn’t seen the film is obliged to remedy that immediately), Updike wrote a total of sixty-one books in his lifetime and vowed to write at least three pages a day about anything. He told the Paris Review that he would “write ads for deodorant or labels for catsup bottles if he had to,” as long as it forced him to put pen to paper.

Updike’s adventures in prose brought him to sample anything and everything: novels, poetry, short stories, nonfiction, journalism (in fact, what is considered by many the best piece of sports journalism of all time), and even cartoons. Yes, cartoons--in addition to being a virtuoso writer, he also had a knack for drawing and attended art school in London after graduating from Harvard.

Always an apt student, Updike graduated high school as co-valedictorian and attended college on a full-ride, yet the rigidity of University life failed to ignite his imagination, and he ultimately found the whole system a bit stifling. At the age of 25, he left NYC and a writing job at the New Yorker to live at the Massachusetts seaside with his second wife, Martha Updike. They hunkered down on an eleven-acre estate for five decades, giving Updike the inspiration that he needed to finally complete his first novel.

For this issue of Time Magazine, superstar pop-artist Alex Katz was tasked with capturing Updike’s likeness and personality, which was undoubtedly a tall order considering Updike’s status as one of the greatest literary figures of all time. Katz honed in on his face, framing it with vibrant green foliage as a reference to the years that he spent living in rural Mass. Although the greenery gives the great outdoors pride of place, the actual sitting took place inside Updike’s study, within which Katz found the atmosphere ideal. He claimed that the lighting in the final painting was “the most realistic aspect of all”.

In an effort to identify the “gestures that belong” to his sitters, Katz engages them in a conversation for nearly the whole sitting, keeping their faces animated as he draws. Writers are usually good talkers, so maintaining a steady conversation with Updike didn’t prove difficult; their chatter was as relaxed and easy as a breezy Summer’s day.

Updike never mentioned or made a comment about whether he liked the painting or not, but as usual for an artist with a unique outlook, the public met the piece with mixed reactions. Some claimed that the portrait was washed out and that Katz missed the subject’s warmth and vibrancy. Others claim that the portrait captures Updike’s personality perfectly: “Never jaded, always new, alive, intelligent, and marvelously controlled.”

I’m sure that this criticism didn’t deter Katz in the slightest. He never intended to create a photorealistic portrait. “Without a good likeness, you don’t have a good picture” he philosophized, “but you can wreck a painting very easily if you get obsessive about likeness.” In a nutshell: it needs to look like the person represented but without taking away the style that makes Katz’s work unique. Pretty much any post-Renaissance portraitist would agree, I’m sure.