More about James K. Polk

Contributor

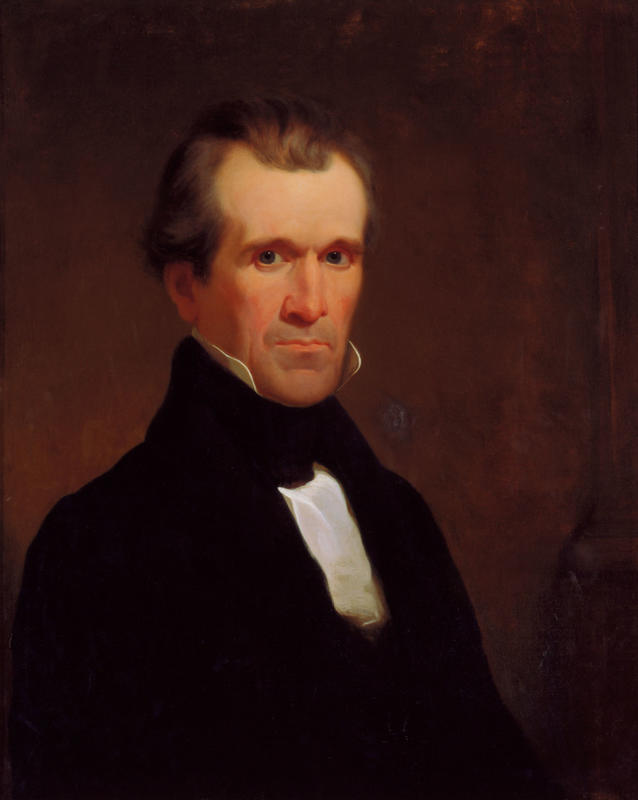

James K. Polk, the 11th president of the United States, is the man painted here by Kellogg.

Polk was born November 2nd, 1795 in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. The Polks moved to Maury County, Tennessee in 1806, where James spent most of his formative years. He never had formal education after common school due to illness, leaving him with private tutelage as his only means of keeping up intellectually. Through the sweat of his brow, he managed to pass the entrance exams for the University of North Carolina at the age of 20. By 1818, he graduated with degrees in the classics (Greece and Roman work) and mathematics. He returned to Tennessee to practice law. By 1820, he passed the bar exam.

The Southern-fried lawyer was not only a devoted Democrat and supporter of Andrew Jackson, but possessed a gift of gab that would earn him the moniker “Napoleon on the stump.” Most of Polk’s rise to power was assured by his wife, Sarah Childress Polk, whose high social standing as the daughter of a planter, disdain for domestic work, and desire for a childless marriage allowed the spotlight to only get brighter on James’ career. She was so politically active that she was nicknamed “the Presidentress.” As a Presbyterian, she had a conservative view toward leisurely activities, even forbidding the playing of music on Sundays. She was also the first to introduce gas lights into the White House.

He entered into the Democratic Convention in Baltimore, Maryland in 1844. Against more prominent names such as van Buren and Buchanan, Polk was content to have a place as vice president. No one expected him to win. However, just like today, the Democratic candidates had their own grievances against each other, and the party would have none of that. By election day, James K. Polk became president of the United States.

At the time, he was the youngest president to take office and his term was marked by a bunch of territorial disputes with both Great Britain and Mexico. The former concerned the territory of Oregon, which back then encompassed a sizeable chunk of the Northwest. It was resolved quickly by a split on the 49th parallel, forming the northern border that would separate the U.S. from Canada in 1844, despite the Democrats’ desire to extend U.S. claims all the way to the 54th.

The latter was much bloodier. Polk offered twenty million dollars plus settlement of damage claims owed to Americans in exchange for the territories of California and New Mexico. At the time, those territories comprised half of Mexico, and the powers that were at that time could not sell it off and stay in power. The request was denied. To “persuade” them further, General Zachary Taylor was sent to the disputed area. The Mexican troops, seeing this as a sign of aggression, opened fire, and thus started the Mexican War in 1846. The Americans quickly resolved that too, winning a streak of victories and occupying Mexico City for a time. By 1848, the Mexicans compromised and agreed to surrender, giving the U.S. two more states. He died in June 1849, overworked from his term, but leaving the country with territory that would become a factor in a civil dispute that would end bloodily decades later.

Sources

- “James K. Polk.” n.d. The White House. The United States Government. Accessed February 28, 2019. https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/james-k-pol….

- “POLK, James Knox.” n.d. US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. US House of Representatives. Accessed February 28, 2019. https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/P/POLK,-James-Knox-(P000409)/.

- Robinson, George Clarence. 2018. “James K. Polk.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. October 29, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-K-Polk#ref5829.