More about Eugène Manet on the Isle of Wight

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

Edouard Manet said of Berthe Morisot’s painting, “this woman’s work is exceptional, too bad she’s not a man.”

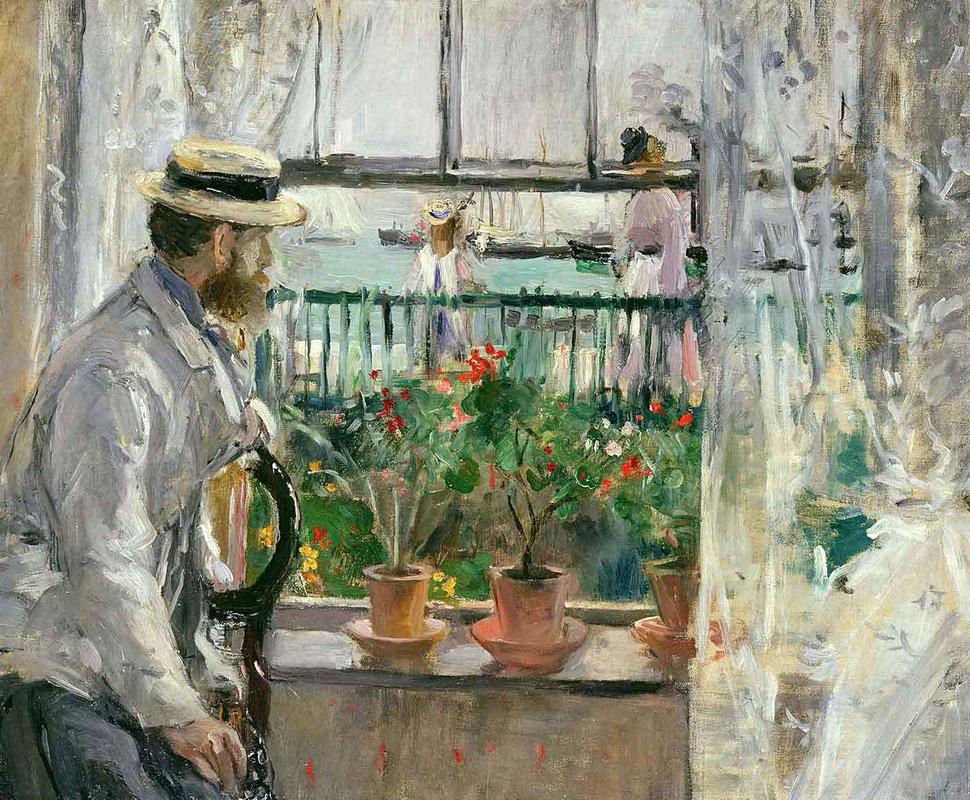

On one hand this might sound like some real crap, but he probably meant, "My homie rips at painting, I hate knowing she’s gonna get sidelined after she dies bc she doesn’t have a penis." Berthe and Edouard had a close professional relationship, Edouard took her advice on painting outside with a bright palette, and Berthe seems to have taken his words about man-ishness to heart. In this painting she positions her partner Eugène Manet (not to be confused with his brother Ed) as the archetypal painter surveying a scene. But Eugène didn’t paint, so Morisot is exchanging herself with the husband figure, flipping her gendered role, if not gender itself, leading one critic to call her the “drag king of impressionism.”

Berthe was committed to this gender bending outside of her painting too. Eugène was the stay-at-home dad taking care of the baby while Berthe was the professional (I mean, the haute bourgeois don’t need to work). She was the only woman included in the controversial First Impressionist Exhibition, which is to say that she was as good as Claude Monet and as serious as Elizabeth Nourse. Berthe had no interest in painting just for the fun of it. She said that this window on the Isle of Wight was “very pretty to see, very ugly to paint” and that as a result she referred to what little she did paint as “frightful.” Which is the kind of self-deprecating ambition and self-serious malaise that makes for good paintings. When she and Eugène were married she made sure, in no uncertain terms, that her painting would continue uninterrupted and that she would do so under her maiden name.

Her pursuit of an artistic career, at the time and for her class, is a little like Paris Hilton’s pioneering of pseudo-sex-work reality television—which is to say, a scandal. An early teacher called her artistic determination “almost a catastrophe” for her bourgeois family. But her daring, both in spurning her parents’ expectations and in her wild brushwork, was pretty much exactly the opposite of a catastrophe for impressionism-heads. How else would we get to see French high society through the eyes of a wylin'-out painter/secret-drag-king?

Sources

- “Berthe Morisot: Inventing Impressionism.” ArtFundUK. YouTube, video. Posted March 5, 2015, 02:46. Accessed May 21, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mupxAAjAiWM

- Cascone, Sarah. “Once Overlooked, Impressionist Painter Berthe Morisot Is About to Be Everywhere – Here’s Why.” artnet news. May 16, 2018. Accessed May 21, 2018. https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/impressionist-master-berthe-morisot…-

- Gopnik, Blake. “Berthe Morisot, Who Manned the Canvas.” Washington Post. January 16, 2015. Accessed May 21, 2018. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A9685-2005Jan14.html?nav=…

- jonathan4585. April 13, 2012. “Eugène Manet on the Isle of Wight and Eugène Manet and His Daughter in the Garden by Berthe Morisot.” my daily art display. Accessed May 21, 2018. https://mydailyartdisplay.wordpress.com/2012/04/13/eugene-manet-on-the-…