More about Bill T. Jones

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

Mapplethorpe was not the only gay artist in the nineties to have a provocative career.

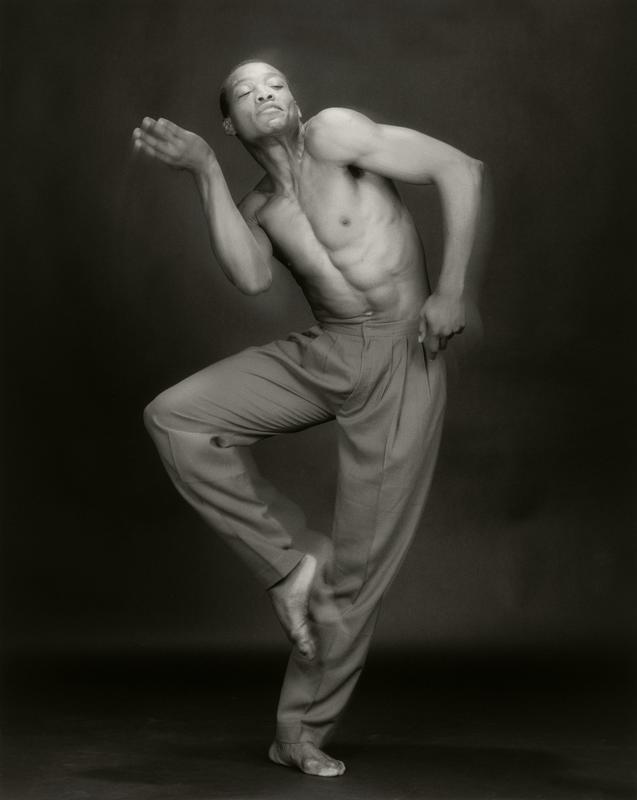

In spite of his reputation as a controversial avant-garde dancer and choreographer, Bill T. Jones started out as a jock. He grew up on a farm in rural New York with eleven siblings, and in high school, his excellence on the track team won him several awards. When he went to college, however, Jones discovered dance, which quickly took priority for him over athletics. Like a campy inspirational coming-out story, while he was skipping track practices for dance class, he discovered his sexuality and met his first long-term boyfriend. The two collaborated on dance throughout their college career and beyond, eventually forming the Bill T Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, named after the founding couple. Jones’ dance pieces were immediately radical in the way that they drew from his life experiences as a gay black man, as well as challenging the boundaries of performance with unusual choreography, audience interaction, and experimental music selections. He also distanced himself from the overwhelming whiteness and thinness of traditional dance groups, and his company has always been diverse in race and body type.

Jones’ avant-garde work was met with success throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s, and the group was even able to tour Europe, until the company met with tragedy: Arnie Zane died of an AIDS-related illness in 1988 and Jones discovered he was HIV+. The loss of his partner of nearly two decades, and the threat to his own health, dramatically colored the projects Jones took on in the ensuing years. His exploration of illness and loss unexpectedly moved beyond personal tragedy to elevate him to a controversial stardom, with the 1993 dance piece Still/Here.

Still/Here was the peak of Jones’ artistic studies into living with terminal illnesses, such as AIDS and cancer. What drew critical attention was the way he incorporated performers who were actually ill—their bodies were on stage as dancers, and their voices and faces (recorded from nationwide workshops he’d done beforehand) were projected around the space. A reviewer for the New Yorker, Arlene Croce, took issue with this, and wrote a “review” —“Discussing the Undiscussable"—about how she refused to see what she termed “victim art.” Putting aside the problem of how exactly someone is able to qualify an art piece that they refuse to see, her opinion spurred a flurry of argument in the art world.

Some critics agreed with Croce’s condescending article, bemoaning the degeneracy and political commentary of modern art and Jones’ alleged manipulativeness and unoriginality for addressing death and the AIDS crisis so directly. The controversy has parallels to Mapplethorpe’s struggles with censorship and defunding based on the “obscenity” of his photography; in both cases, a conservative public panicked at art that openly depicted, even celebrated, the artists’ marginalized identities. Croce even invoked the photographer, citing him and Jones as artists whose work she rejects because she “pities” them. Apparently the fact that the contemporary artistic community, with its high proportion of gay and queer artists, was affected by the AIDS crisis, was not a welcome realization for homophobic art critics of the '90s.

In spite of disparaging reviews, the public drama brought Jones a new level of fame, and he continues to choreograph and lead his dance company today. In 2017, he was awarded the Smithsonian’s Portrait of a Nation award, for “exemplary achievements and significant contributions to American history and culture.” No matter what a few disdainful critics might say, Bill T. Jones’ successful and provocative career prove that he is far from “undiscussable.”

Sources

- O’Mahony, John. “Body artist.” Guardian (London, UK), June 11, 2004. https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2004/jun/12/dance

- “Portrait of a Nation Prize Recipient: Bill T. Jones.” Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. November 15, 2017. http://npg.si.edu/blog/portrait-nation-prize-recipient-bill-t-jones

- Siegel, Marcia B. "Virtual Criticism and the Dance of Death." TDR (1988-) 40, no. 2 (1996): 60-70. doi:10.2307/1146529.