More about Giotto

- All

- Info

- Shop

Contributor

If Michelangelo, Raphael, Donatello and Leonardo were the turtles of art world, then let’s agree to call Giotto de Bondone Splinter from now on.

He may not have given the turtles one-on-one ninjutsu lessons (or was it painting? I get confused…), but he inarguably laid the foundations for these Renaissance giants to work with. Giotto made a lasting break from the pre-existing tradition of painting, through hours of careful observation and analytical techniques…insert image of a fourteenth century Italian guy poring over a twig with a magnifying glass. Compared to the two-dimensional, flat and formless stuff that artists had been making before, Giotto’s bodies looked real. All that staring and squinting at natural forms made Giotto aware of things like volume, perspective, shadows, i.e. the stuff of foundation year drawing classes in art schools today. You can see the evidence of his people watching and nature gazing in works like Madonna Enthroned.

All this shouldn’t lead to you thinking that Giotto achieved this natural effect during his twilight years. Giotto was pretty much a natural at nature from the start. He worked as a shepherd’s boy whilst young, and one of the famous masters of painting in Florence at that time, Cimabue, caught him happily sketching sheep on a rock during this stint. They were probably good enough to make Cimabue go “Baaaah." Or, bad jokes aside, they secured Giotto a place as Cimabue’s apprentice. Giotto also impressed the church with his talent, just by sending the Pope a freehand drawing of a perfect circle. And thus, a proverb was born which went something like: “You are rounder than the O of Giotto,” which is a compliment, even though it sounds like a mean thing to say to a fuller-figured friend.

And in case you’re still picturing Giotto as an oversized anthropomorphic rat named Splinter thanks to my glowing analogy from before...well, you may not be too far off. Contemporaries went so far as to say that “there was no uglier man in the city of Florence”, and that his children didn’t fall too far from the tree either. Legend has it that Dante paid Giotto a visit once and saw his rather unattractive children. Like a good-mannered guest, he asked how someone who paints such beautiful pictures could produce such unfortunate looking children. Giotto responded, “I made them in the dark.”

Featured Books & Academic Sources

The following is an excerpt from "Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects, Vol. I" by Giorgio Vasari, originally published in 1550:

That very obligation which the craftsmen of painting owe to nature, who serves continually as model to those who are ever wresting the good from her best and most beautiful features and striving to counterfeit and to imitate her, should be owed, in my belief, to Giotto, painter of Florence, for the reason that, after the methods of good paintings and their outlines had lain buried for so many years under the ruins of the wars, he alone, although born among inept craftsmen, by the gift of God revived that art, which had come to a grievous pass, and brought it to such a form as could be called good. And truly it was a very great miracle that that age, gross and inept, should have had strength to work in Giotto in a fashion so masterly, that design, whereof the men of those times had little or no knowledge, was restored completely to life by means of him. And yet this great man was born at the village of Vespignano, in the district of Florence, fourteen miles distant from that city, in the year 1276, from a father named Bondone, a tiller of the soil and a simple fellow. He, having had this son, to whom he gave the name Giotto, reared him conformably to his condition; and when he had come to the age of ten, he showed in all his actions, although childish still, a vivacity and readiness of intelligence much out of the ordinary, which rendered him dear not only to his father but to all those also who knew him, both in the village and beyond.

Now Bondone gave some sheep into his charge, and he, going about the holding, now in one part and now in another, to graze them, and impelled by a natural inclination to the art of design, was for ever drawing, on stones, on the ground, or on sand, something from nature, or in truth anything that came into his fancy. Wherefore Cimabue, going one day on some business of his own from Florence to Vespignano, found Giotto, while his sheep were browsing, portraying a sheep from nature on a flat and polished slab, with a stone slightly pointed, without having learnt any method of doing this from others, but only from nature; whence Cimabue, standing fast all in a marvel, asked him if he wished to go to live with him. The child answered that, his father consenting, he would go willingly. Cimabue then asking this from Bondone, the latter lovingly granted it to him, and was content that he should take the boy with him to Florence; whither having come, in a short time, assisted by nature and taught by Cimabue, the child not only equalled the manner of his master, but became so good an imitator of nature that he banished completely that rude Greek manner and revived the modern and good art of painting, introducing the portraying well from nature of living people, which had not been used for more than two hundred years. If, indeed, anyone had tried it, as has been said above, he had not succeeded very happily, nor as well by a great measure as Giotto, who portrayed among others, as is still seen to-day in the Chapel of the Palace of the Podestà at Florence, Dante Alighieri, a contemporary and his very great friend, and no less famous as poet than was in the same times Giotto as painter, so much praised by Messer Giovanni Boccaccio in the preface to the story of Messer Forese da Rabatta and of Giotto the painter himself. In the same chapel are the portraits, likewise by the same man’s hand, of Ser Brunetto Latini, master of Dante, and of Messer Corso Donati, a great citizen of those times.

Sources

- Vasari, Girogio. "Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects, Vol. I" (London: MACMILLAN AND CO. LD. & THE MEDICI SOCIETY, LD. 1912.) 71-72.

Featured Content

Here is what Wikipedia says about Giotto

Giotto di Bondone (

Italian pronunciation: [ˈdʒɔtto di bonˈdoːne]; c. 1267 – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto (UK: /ˈdʒɒtoʊ/ JOT-oh, US: /dʒiˈɒtoʊ, ˈdʒɔːtoʊ/ jee-OT-oh, JAW-toh) and Latinised as Giottus, was an Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the Gothic and Proto-Renaissance period. Giotto's contemporary, the banker and chronicler Giovanni Villani, wrote that Giotto was "the most sovereign master of painting in his time, who drew all his figures and their postures according to nature" and of his publicly recognized "talent and excellence". Giorgio Vasari described Giotto as making a decisive break from the prevalent Byzantine style and as initiating "the great art of painting as we know it today, introducing the technique of drawing accurately from life, which had been neglected for more than two hundred years".

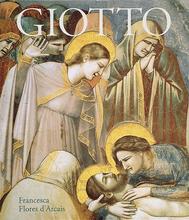

Giotto's masterwork is the decoration of the Scrovegni Chapel, in Padua, also known as the Arena Chapel, which was completed around 1305. The fresco cycle depicts the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ. It is regarded as one of the supreme masterpieces of the Early Renaissance.

The fact that Giotto painted the Arena Chapel and that he was chosen by the Commune of Florence in 1334 to design the new campanile (bell tower) of the Florence Cathedral are among the few certainties about his life. Almost every other aspect of it is subject to controversy: his birth date, his birthplace, his appearance, his apprenticeship, the order in which he created his works, whether he painted the famous frescoes in the Upper Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi, and his burial place.

Check out the full Wikipedia article about Giotto